Borrowed Sleep

Interview with Miyuki Oka. An unusual day in the background of life

A few words about…

* For the safety of all concerned, some words have been replaced from the original text by mutual consent. Although all parties involved understand the true essence of things and refuse to recognise the violent nature of the present events.

It’s been over a year since the last article was published under the auspices of Gendai Eye. It’s been a while since I’ve had guests, opportunities to focus on conversations with them, let alone the right words for those conversations, but let’s try again, shall we? I’m pleased to introduce Japanese artist Miyuki Oka, who we’ve been chatting with quite a bit over the course of this year. Before moving on to the conversation itself, it seems necessary to say a word or two about her projects, some of which get under my skin with their delicacy and inventive approach to realising the subject matter.

Of course, I would not want to prepare the shackles of “science art” for Miyuki, as this would immediately relegate many of the qualities of her work, but her instrumental use of technology is very closely linked to her personal interest in the world of information and the sense of time. The notion of a cycle or the realisation of periodic patterns is also felt in the earliest projects “Decomputation: Periodicity” (2018), where the algorithm created gave the laser beam its own track of movement, which the viewer, if they looked closely, could detect for themselves. This can also include the issue of energy conversion, as in “To handle (A)‘ (2021), where the movement of wind was converted into magnetic and electrical states that changed the movement of objects in the room and on the monitor screen.

From the mechanical and spatial the idea evolved towards representations of memory and grief in the future, as in the project “Ikitoshi‘ (2019-2020), a reflection on the theme of memory and grief in a post-anthropocentric world where humans are not privileged over other living organisms. To this end, the artist develops a kinetic system that functions by generating electricity from the activity of microbes in the soil. A flower created from the skin of a deceased person moves through the soil, leaving behind its remains, thus creating new soil and energy, continuing the cycle.

An interest in the outside world, ecology and its data in history, occurs in the recent project “Greenhouse Marathon” (2022), dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the Munich Olympics and the events of then recently held Tokyo Olympics. By linking the project to Sapporo, where the artist was born, she attempts to demonstrate how climate change occurred over a large time period, as the marathon of the 2021 Olympics was held in Sapporo as the temperature in Tokyo exceeded the acceptable guidelines. The project-construction of a greenhouse where the runner was located and temperature sensors, depending on the temperature-showed the year, date and time when a particular value was recorded over the past 120 years of the Olympics.

It is all the more surprising to witness the formation of the current project “Borrowed sleep / Taking photos (000000-235959, 20210224 — 20230224)‘, completely different from her previous works. ‘Borrowed sleep’ is a space of time and destinies, in which documentary testimonies of people from Ukraine and Russia, whose lives were changed by the so called special military operation, are enclosed. Stories from several thousand photographs taken personally by the project participants are intertwined with each other in 24 hours of video or, as the artist specifies, in 86400 seconds. Showing the changing everyday life from February 2021 to February 2023, this ongoing project highlights special moments from the data set, asserting that life goes on, that this is not a documentary-dry look, but an interested, willing to hear and see.

We will talk about this project, the peculiarities of its creation and implementation, and its further development with Miyuki Oka, to whom I am very grateful for the wonderful moments of our communication and today’s dialogue.

Interview with Miyuki Oka

Gendai Eye: How do you feel after completing this project, are you satisfied with the result?

Miyuki Oka: I am very pleased with the result and happy that I was able to hold the exhibition at this time of year. I wanted to do it as soon as possible as the conflict is still going on.

GE: After showing this exhibition in Tokyo, you are planning an additional show in Sapporo. What is the status of these plans?

MO: I still don’t know how and where to make this exhibition. I think an article about my work will appear this week and I will send it out to a few galleries in Sapporo so they can see what I do. It would be an opportunity to get some space and funding.

GE: This work of yours differs from your previous projects. How do you see this work among your other works at the moment?

MO: Many people said that it’s so rare for me to make such an ongoing work with a political context. In my previous works, as you can see, I usually focused on the human and the non-human world. But I’m really interested in the relationship between individuals and others, which is why this work came about. For me it’s a very continuous interest in how I can make connections between myself and others, it also has to do with the human world and politics.

GE: What was the initial trigger for you to create this project? How did you decide to do this work?

MO: I created the format for this work last summer. I started with my own photos, studying Google Photos. Sometimes it shows photos from the past, some random albums and moments. And I was surprised that photos taken on a smartphone don’t look very old, when I take photos of food, a cat or my dog, they don’t look very old. You don’t see any difference between photos taken today or two years ago. That’s how I started to think about time.

My grandfather died about three years ago and he left his phone with his photos on it, and then I made a 24-hour video of his photos. I also used photos taken by my mum using her smartphone during the same period as those left by my grandfather, which at the time were interesting to me because they captured some extraordinary and unusual days in her life. For example, my mother took care of her dog, before he died, she took a lot of photos of him, from early morning until night. When I encapsulated her life of four years, the video highlights her unordinary day. This format allowed me to meet someone’s extraordinary days as an extension of their ordinary days. This is how I use this format to capture what is happening in Ukraine and Russia.

GE: How can you describe in general words this special moment in the photos of Ukrainian and Russian refugees? What does “a special moment” mean for them? Is it related to the special military operation or is it something personal?

MO: For this project, I’m focusing on the 24th of February. For me, this day is extraordinary and unusual. But everyday life goes on, the video doesn’t highlight the 24th of February but shows its impact on everyday life. At first I thought the work would highlight one day, but rather the difference is subtle and hard to notice. But when you watch the video for a very long time, you can see this difference and what happened to the person’s life.

GE: Please tell me, did you have an opportunity to communicate with the audience of the exhibition in Tokyo, what did they think about your work?

MO: The most common impression is that they learn that everyday life goes on. After reading the exhibition flyer, people expect something more documentary. And what I show is the ordinary days of their lives. At first they are a bit confused, but then they continue to watch, sometimes finding out that the participant of the exhibition changed his place of living and some other things. It makes me happy to see this kind of reaction. In this work I don’t intend to judge or support any nation or ethnic group, but rather to learn about individual experiences.

GE: If we are talking about the issue of perception of the special military operation that Russia started in Ukraine, what do you see as the difference in the reactions and judgements of people in Japan and Germany, given their different geographical proximity and involvement in this story?

MO: I also thought about doing this exhibition in Germany, but the German community is culturally, geographically and politically closer to what is happening. I think the audience will be more sensitive to this issue. I suppose a real distance, including physical and psychological distance, between the viewer and the participant is important. I guess that some participants would not want to share their photographs if I had chosen to exhibit in Germany. Distance is very effective and important. The Japanese are distant and their reaction to this particular conflict is less intense than in Europe.

GE: And there’s also probably a difference in the audience, because Europeans are much more eager to take photos and videos at the exhibition and don’t really care about any bans, so anonymity is completely destroyed in this case.

MO: Yes! But I hope I can somehow show it in different countries around the world.

GE: Will this project continue and collect new material? What is the end point of this project for you?

MO: I think I will work with the project, trying to take a broader time period. As for the end period, I don’t know exactly, but it will probably be related to the day when the conflict ends. But for me it is interesting to show this project in other parts of the world and to study people’s reactions to participant’s lives and to political things.

GE: We often encounter the stereotype that the image of technology, the notion of algorithm — all of these things rhyme with depersonalisation and loss of the emotional — how do you manage to combine these things in your case and make the project as personal as possible on the basis of so much data?

MO: I think it’s important for me not to create a comprehensible narrative out of a huge amount of data, but to create poetry that remains concrete and complex and very open to interpretation by the audience. What I did for this exhibition was to use one smartphone for a person to show the photographs. That was very important to me. If I had only used one display to show all the photos, it wouldn’t have worked. It would mean I was just using the photographs as mere image material, and that would erase the individuality. If, however, I display them that way and let the viewers meet the participants of the day through the actual object, a smartphone, it would really work in this case.

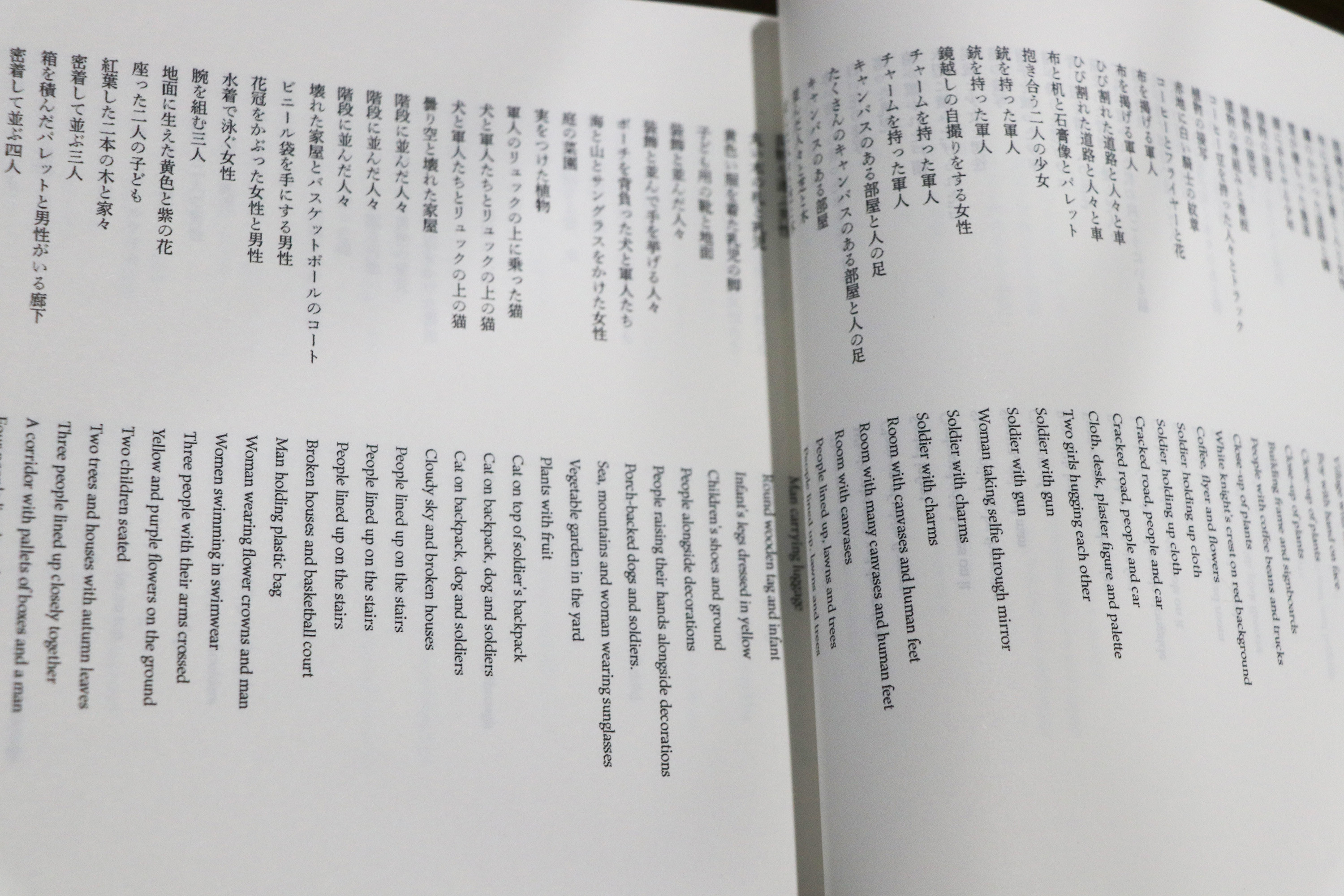

I also made a one-line description of all the photos and printed them out in chronological order. There were around 4000 photos and it looked like a book. The program that I made gets the time data from the photo file and automatically makes 24-hour video, so you don’t have to go through all the photos to run it. But I think it’s very problematic, and I wanted to see all the photos as an artist doing this project. I wanted to leave a trace that I saw these photographs. That’s how I tried to avoid depersonalising the data. I am an artist and a viewer at the same time.

GE: There is another interesting aspect that I think is important and related to your project, which is that all data, including photos and videos, can be easily manipulated, changing or deleting the dates and locations where the material was shot. What do you think about the manipulation aspect, how does it fit the format of your current work?

MO: This was something I noticed when I was working with these photos. Two participants who knew each other had the same photo, but with different data and time record. The photo was probably shared and re-uploaded. I had only used my own and family photos before, so I didn’t have this problem and could easily ask if they had changed anything or not. It is interesting that change of the data is not affecting photo appearance. I want to look further into this issue and research how the data is changed.

GE: Where did the name “borrowed sleep”, “biological rhythm” in the description come from and what does it mean in the context of the work you created?

MO: “Borrowed Sleep” is a phrase from an essay style text “Tabi no e (Picture of a Journey)” by Tatsuo Hori [1]. He describes how when he woke up while travelling, surrounded by unfamiliar things in a hotel, he felt he had borrowed someone else’s sleep. When I see some random photos taken by someone, I sometimes feel like I’ve forgotten who took them. Was it me or someone else? It seems to me that this confusion of recording and memory is consistent with his text. As for “biological rhythm”, when I was making this format, I was neither a student nor an office worker, I was nobody at all. And at that time I lost my sense of belonging to time, dates and weeks seemed like nothing to me and only the morning and night cycles felt real. I was reading a book about time, and it said that sleep is the sister of death, and there is a correspondence between life and death, wakefulness and sleep. This work shows life, the way we live the day and our lives.

GE: Your lifelong interest in the world around you, in learning about it through technology, at what point did you also become interested in talking about the connections between people, when did it start for you?

MO: I think it was in university when I was studying agricultural science, I was into biology and chemistry before I got interested in art. I live in Sapporo, nature is very close, hiking and other things are quite normal for me. I’m more interested in non-human things than humans.

GE: Has your approach to work been affected by the COVID-19 epidemic?

MO: The COVID-19 experience has definitely influenced my work. During the lockdown period, online status was the only evidence that you were living. If you leave any trace of your life on social media, then something has happened to you. This got me thinking about the online record, the digital record and the physical self.

GE: Tell me, again in the context of influences and your own feelings, how Sapporo affected you? You repeatedly notice that contemporary art was not institutionally well-developed there, but you still had an interest at some point.

MO: Sapporo is a beautiful and clean city, but a bit boring, like many regional cities in Japan and around the world. Sometimes that’s a good thing, but I don’t think there are many marginal spaces here for the spontaneous emergence of something different or new. So I’ve been using my computer as a playground, and that fact has probably influenced my work — I like to try to be personal, but trying to connect with something that is far away from here. To be honest, I don’t have a particular attachment to a location, not just Sapporo, but I’m a nomadic person in general. I have internalised Sapporo and somewhat like it because I’ve lived here for a long time. One special thing about Sapporo is that it’s a new city. Hokkaido was colonised by settlers from mainland Japan, and Sapporo is the centre of that land. Having familiarised myself with the context of a post-colonial way of life or way of making something, I feel we have a lot of things we can try here. I see young artists in Sapporo trying to create their own place in Sapporo and working with this colonial context.

GE: When did it start?

MO: One recent topic of great controversy was the demolition of Centennial Memorial Tower [2], which was decided on in 2018. The decision was due to the rising cost of maintenance due to ageing. The monument was dedicated to the development of Hokkaido, but has also been criticised as a symbol of assimilation policies and discrimination against the Ainu people. There was a group exhibition on this tower in Sapporo in the same year.

GE: What are your plans for future works?

MO: The format I have created is new to me and to people living in this era. I hope that people can use this format on their own for their own personal or political purposes. It is hosted on GitHub so anyone can use it. In addition to this project, from January I am inviting an artist collective from Munich, with whom I have already worked with during my residency, to work in Sapporo. They collect materials from artists, galleries and theatres, and distribute them to artists and students. I invited them, and we’re going to try to start a cycle of materials for artists in Sapporo. It’s very experimental, and I don’t know how many people will be interested in it. Having a project like this in Sapporo is very good for the place, and its purpose is to engage in dialogue with different cultural institutions on sustainable and new ways of creation in regional areas.

---

Notes:

[1] Tatsuo Hori (1904-1953) was a Japanese writer, poet and translator. Best known for his work “The Wind Rises”, which was screened by Hayao Miyazaki in 2013 under the same title.

[2] Centennial Memorial Tower was built in 1970 to mark the centenary of the exploration of Hokkaido, at the time it was understood as a token of gratitude for the labour of the colonisers in developing new territories. The design of the 100-meter tower was also symbolic of the rapid development of the future, which was an extremely popular subject at the turn of the 1960s and 1970s. In 2018, due to the deteriorating condition of the site and the cost of its maintenance, a public survey was conducted, which resulted in a majority in favour of dismantling the tower. In addition to the material component, the tower has been heavily criticised for its assimilationist and discriminatory message towards the Ainu, ignoring their status and contribution to the development of the island. Some similar discussions took place in 1969, when it was proposed to honour specific individuals and indigenous peoples of Hokkaido, but the idea was ignored. Despite continued protests from conservatives who continued to criticise the idea of demolishing the tower and made discriminatory statements against the Ainu, the building was dismantled in 2023.