Sign of the Times # 5. Restoring time

In a row, this is the fifth dialogue that comes out as part of the “Sign of the Times” series, where I continue to consider, together with my interlocutors, different ap-proaches to studying and comprehending history through art. Obviously, and this can be seen from previous articles, the difference in approaches of each of the artists is significant, some turn to the fetishization of objects of the past, others reproduce the moments of the past, and there are those who manage to catch witnesses of important events.

Hikaru Fujii, without a doubt, occupies one of the leading places, if one imagines such, among those artists who work with the subject of the history of their country. This was especially convincingly demonstrated by the recent pair exhibition (Tokyo Contemporary Art Award 2020-2022 Exhibition), where Hikaru Fujii, together with the artist Chikako Yamashiro, addressed the theme of war and its trace in the subsequent historical perspective in their projects. His eye looks not only for specific plots and stories, but also refers to the socio-political system as a whole, stretched between generations in different time layers. In this dialogue, we will focus on several projects and talk about editing history and its generational burden.

Thanks to Hikaru Fujii for his patience and taking the time to prepare this conversation.

Russian version / Русская версия

Interview with Hikaru Fujii

Gendai Eye: Can you, based on personal experience, tell us at what point in time you became interested in the history of your country and its individual episodes? I always find it very interesting when you are taught some basic history at school or university, but then you make personal discoveries that turn your idea of historical integrity and quite often the history of the family and its individual members joins this.

Hikaru Fujii: Let me tell you about my childhood. At the elementary school I attended, I sang the “national anthem” at various events, but one day my father said, “They don’t sing the national anthem at schools in Okinawa”. At that time, I had only a touristic image of Okinawa as “beautiful southern islands”, but I then learned about the history of grief and anger of the peo-ple of Okinawa who were forced to make sacrifices during World War II. My father said, “Decide for yourself whether to sing the national anthem or not”. As hundreds of students lined up to sing the national anthem, I remained silent. When I asked myself the ethical ques-tion, “Shouldn’t I sing?”, I lost my voice. At the same time, since I was an ordinary child attending a Japanese school, I also felt a sense of duty to sing like everyone else. Therefore, I think my silent lips moved slightly. There was the distorted body of a boy torn between the national anthem celebrating the reign of the emperor and the harsh history of Okinawa.

---------------------------------

This work is an interplay of footage edited by the United States Army to internally share information regarding Japan’s educational system, and documentary footage of a workshop conducted by the artist in Korea. The artist’s soft yet tyrannical instructions are a metaphor for the relations between the three parties of the United States, Japan and Korea, and the objective yet one-sided narration of the documentary footage is overlaid with the images of the disciplined Japanese students in the film. The latter half of the film depicts Korean students who, after viewing war-related images invisible to the audience, are instructed to reenact the footage they have seen. They become increasingly enthusiastic, going beyond the instructions of the artist toward creating their own actions. The work depicts totalitarianism and education, nationalism and resistance, and the fluctuation of the gradient between. (The Educational System of an Empire, 2016)

---------------------------------

GE: Do I understand correctly that the first work that would deal with the historical aspect is “The Educational System of An Empire”? In it, you address the topic of historical memory, or rather its elements, which can be shuffled and interpreted depending on the circumstances and the benefits from them. Has it become clearer to you how to work with this asymmetric system and is it possible to optimize it, somehow record and broadcast history?

HF: There have been works dealing with events of the past era, but they coincided with the time when the “history” of patriotic sentiment was officially announced at schools, upon the command of the recently murdered former Prime Minister Abe. The “negative heritage” of the imperial era began to be removed from textbooks as a hindrance to the formation of pat-riotism. Abe was trying to build a huge sculpture of the lost empire in the hearts of children. On the other hand, Asian countries, which were once forced to be falsely united as “brothers” to protect the Asian region from the invasion of Western powers, opposed this. To produce this work, I visited Korea, which in the past was colonized and forced into a Japanese educa-tion system.

I will answer your question with the evaluation of another country that is hostile when it comes to the issue of historical recognition; that is, Korea. My work also keeps a distance from victim nationalism. It’s a cold approach. Still, this was accepted locally. The National Museum of a “Hostile Country”, headed by Westerners, has decided to acquire this work.

Then what about Japan? Although this work was exhibited and stored in a private museum, the National Museum actively considered acquiring it, but gave up. In Japan’s state-owned art museums, which are supervised by government officials and structurally unable to guar-antee independence, invisible political powers that we are unaware of are at work. Here is the criticality of the potential of “The Educational System of An Empire”. The “aesthetic system” supervised by the ruling party, which only exists at a certain point in time, limits the open future of art.

GE: In “Record of Bombing” you are in direct contact with those who had to survive the bombing of Tokyo and catch all the terrible destruction that affected people and the city. And in this regard, you are no longer working with archival material, but with those who can give you their personal stories directly. Do you have any interest in capturing stories in this vein?

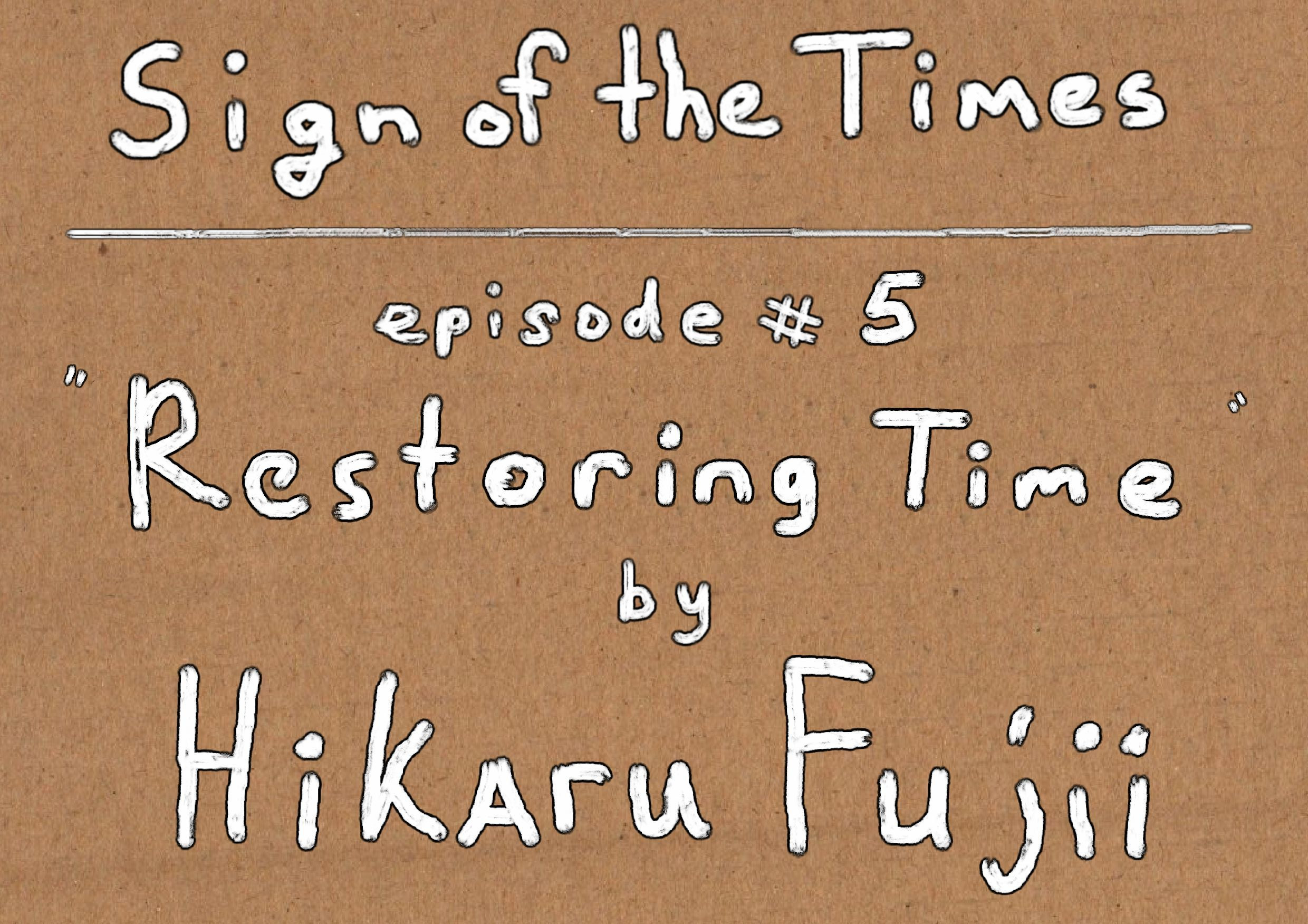

HF: No “unconditional museum” exists in the past or present. Today’s “censorship” does not originate from a particular central organization but continues to work in a network of social relationships. The question is how to overcome the multiple “self-censorship” that limits the spread of the work. This work approaches a politically sealed war archive. It was an attempt to “imagine” with the survivors 5040 historical materials that could not be seen, that is, could not be remembered. Let us reconsider your question from the perspective of “imagination”.

---------------------------------

The bombing of Tokyo by the US military on March 10, 1945 killed around 100,000 people and rendered the entire downtown area of the city a scorched earth. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government enacted an ordinance in 1990 to designate this day as “Tokyo Peace Day.” The “Tokyo Peace Memorial Museum Basic Concept Advisory Committee” was established in 1992, and in 1994, the “Tokyo Peace Memorial Museum Basic Plan” was announced. Over 5,000 artifacts and documentary materials were collected in preparation for the museum’s opening, and video materials were also created by filming interviews with 330 survivors of the air raid. However, in addition to the collapse of the bubble economy, the museum became a political issue. Conservative members of the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly opposed the policy of the exhibition, which was to begin with records of bombings by the former Japanese Army during the Sino-Japanese War, claiming it was based on a “masochistic view of history.” The museum’s budget was frozen in 1999. Requests to exhibit the collection materials, still kept in a museum in Tokyo, have not received approval. This work instead displays captions created from the list of collected items and transcriptions of the interviews, following the exhibition plan of the suspended memorial hall. It recreates a “Memorial Hall of the Imagination” which at first glance contains nothing, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo — located in the area the air raid took place. (Record of the Bombing, 2016)

---------------------------------

GE: The project to build a memorial site in Tokyo was frozen in 1999 and has not yet been implemented. In your opinion, if we look at the balance in terms of visits to Yasukuni Shrine or other places associated with militarism in their own way, and the number of museums of peace and memory, what can be said about this ratio in recent years?

HF: No matter how widespread the attacks on museums dealing with “negative heritage”, there are geopolitical limits. One example is hidden in Yasukuni Shrine, which is considered to be a sacred place for patriotism. The history descriptions displayed in the Yushukan muse-um within the shrine are different in Japanese and English. The latter is “censored” by the US Embassy. In other words, the military ambitions that spread here are heteronomously deter-mined by the will of the American state. Japan’s rearming (or increased defense spending) is integrated with the US military presence that aims to restrain China in the Indo-Pacific wa-ters. It is inevitable that my work often reflects the presence of America.

GE: What does the video format give you when working with the subject of memory and history? How important is the format of accessing archival materials and combin-ing them with your own for you?

HF: My job is to assemble not only videos but also photos, sounds, documents, etc. Spatiality is essential for that, but the audience will experience seeing and listening to the story (narrative) in the “installation”. The format is not unrelated to my partiality for “Histoire (s) du cinema”.

This goes back to the genealogy of cinéma vérité by anthropologist Jean Rouch and others, and the influence of French culture and cinema is immeasurable, because I lived for 10 years in France. On the other hand, for me, based in Asia where authoritarian tendencies are increasing, it is also a fact that I have been greatly influenced by movies that have overcome multiple censorship systems in the former Soviet Union such as those of Andrzej Wajda. For that reason, I may have noticed the words and actions of director Sergei Loznitsa immediately after the beginning of the “special military operation” by Russia.

GE: Your work with people who are involved in the reproduction of certain episodes of history in your projects, can you say that you simultaneously reproduce the old experience and create a new one?

HF: The credits for my work include the names of dozens to over 100 people, like the end credits of a movie. This is because my work requires extensive research and is supported by a wide variety of activities by many filming staff, diverse performers, and excellent setup teams. Art as a thing is the impetus for the birth of a new community (or team) and the creation of a renewed reality.

---------------------------------

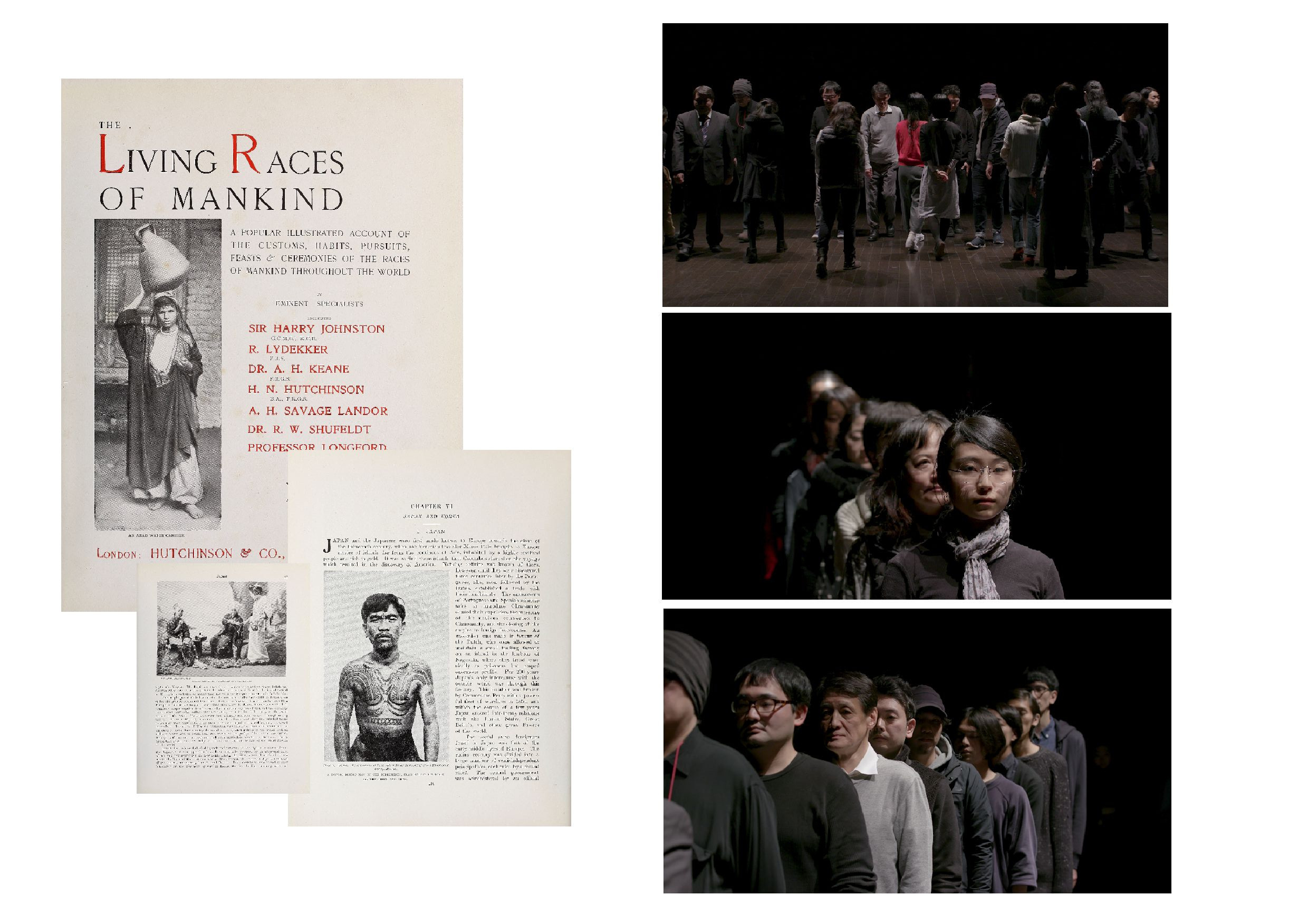

“Kokumin Dojo” (Civilian Training Center) , released circa 1943, was a Japanese state-sponsored propaganda film documenting a series of training and religious rituals used to convert the local Taiwanese people into “imperial subjects” = “Japanese” in Taiwan under Japanese rule. This work attempts a contemporary critical “reenactment” of the lack of self and emotion in the film, where all personal feelings are excluded, representing the values of the militaristic and colonial policies of the time. Young immigrants studying and working in Japan are set on a stage to “change from being non-Japanese, to being Japanese,” while the off-camera commander = director films the collective actions played out on the stage, focusing on the bodies and voices of the four immigrants. Four film works are synchronised with the film “Kokumin Dojo”, resulting in a 5 channel video installation. (Mujō (The Heartless), 2019)

---------------------------------

GE: In “Mujō (The Heartless)”, you also talk about the fact that in addition to linguistic and religious transformations, the people of Taiwan also had to undergo physical retraining in order to become “Japanese”? Can you tell me a little more about this?

HF: The ultimate goal of “Japaneseization” during the war was to mobilize troops. In the postwar “democratic society”, this is externally denied as a form of militarism. However, it can be said that the assimilation policy during the imperial era was continued for foreign residents in Japan. Subsequent economic domination and relentless exploitation targets have been expanded to immigrants created by the global capitalist regime. These are the young immigrants from Southeast Asia who appeared in “The Heartless”. Some are deprived of their "freedom of employment” by a policy called the “foreign technical intern training system”, also recognized as a problem by the United Nations Human Rights Council and in the US Treasury’s “Trafficking in Persons Report” (2021). In addition, it goes without saying that excessive “Japaneseization” is internalized from lifestyle to gestures, and personal expressions are thoroughly monitored through social media and other media.

GE: When you ask people, and most often those nationalities that directly suffered from Japanese aggression during the Pacific War, how do you build contact with them? What do they feel and how painful is it for them to go through what their relatives may have gone through in the past?

HF: The wounds of war ache in people’s hearts longer than the war itself. However, as a social and collective memory, I mentioned earlier that forgetting can be accelerated intentionally. The immigrants who appear in my work are third and fourth generation. They are young people who are “dehumanized” under the Japanese system in a different way than in the past. Erasing the “negative heritage” of the imperial era is linked to the law and power that renders their existence invisible today.

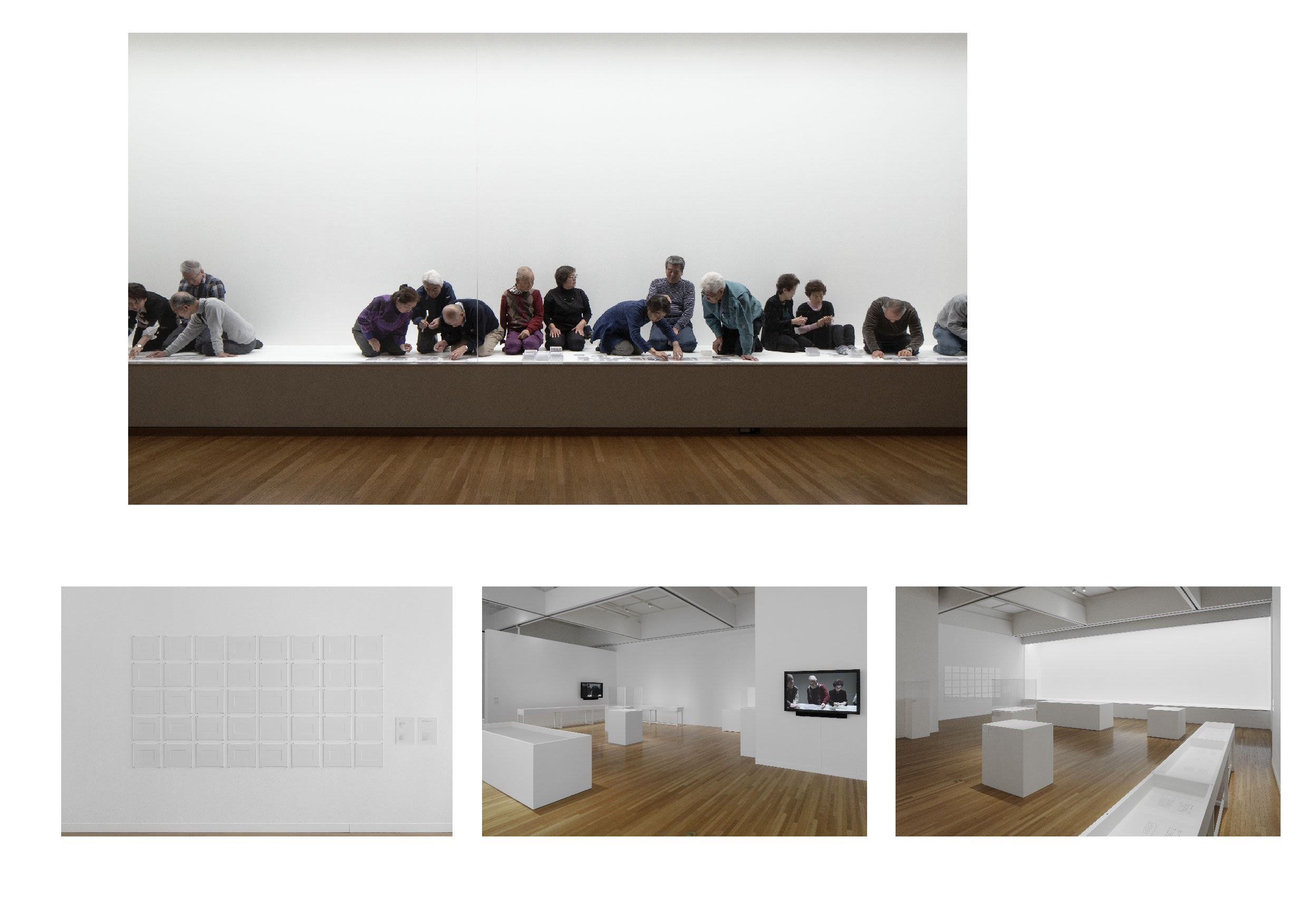

GE: In “Playing Japanese” you refer to the story of the incident around the pavilion of the human races in 1903, when the participants refused to act as exhibits in this exhi-bition. To what extent, in your opinion, did the transfer of the imperial view as a project from the outside contribute to the fact that national hierarchies and the problem of discrimination were gradually built up? And do traces of this process remain in the present?

HF: In the colonial era, when the theory of social evolution was worshiped, the visual device “human exhibition” was a technology that fixed the paradigm of discrimination. It is not difficult to show that the gaze of this empire and the racism represented by modern white supremacy are connected across time and space. Rather, my interest is in those who protested the “human exhibition”. This shows the limits of the intellectual framework of “humanitarianism” at the time. It is to review postcolonial theory and to look at the limits of modern society that deny discrimination, the dark side.

---------------------------------

The Fifth National Industrial Exhibition was held in Osaka in 1903. In addition to buildings for Agricultural Production, Forestry Production, Marine Production, Industrial, Machinery, Educational, Fine Art, Transportation and Animals at the main venue of Tennoji Imamiya, the “Pavilion of the Human Races” was also established. This featured “human exhibits”, as were popular at expositions in Europe at the time, “exhibiting” 32 ethnic Ryukyu (Okinawan) and Ainu people in traditional-style spaces. However, protests by those being exhibited forced a review of the exhibition. Inspired by this incident, this installation is a record of a workshop in which the gaze of the “Japanese people” of the time is reenacted through readings of newspaper editorials. In keeping with the discourse of the time, the work reveals through participants who have been given roles within the framework established by the artist the existence of an internalized gaze toward the other, as well as the structure and multiple layers which reproduce discrimination. (Playing Japanese, 2017)

---------------------------------

GE: We talked about understanding and accepting history through documentary evidence and eyewitness stories. Could you please tell our audience about some of the most key works of art (works, books, movies) that would most fully reveal the topic of our conversation today for you? Is there anything else that impressed you the most?

HF: My latest work revisits the vast collection of war paintings commissioned by the Government of Japan during World War II. After the war, the American Occupation Forces requisitioned them, but war paintings were taboo (or neglected) in Japanese society and their meaning was not delved into more deeply. I worked with art historians to try to connect the political and military debate over the Japanese war paintings to contemporary issues, based on confidential documents of the time stored in the US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). The work also considers the US government’s supremacy in spreading Abstract Expressionist paintings (or “other war paintings”, as symbolized by the CIA’s collaboration with Jackson Pollock) to the world as a weapon of liberal nations during the Cold War.

---------------------------------

During World War II, around 100 prominent Japanese artists served in the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy, producing paintings on the subject of the war waged throughout Asia. Following Japan’s defeat, the United States occupation forces seized 153 of these paintings, which were since kept at a distance from the Japanese people in line with the demilitarization of Japan. There was hesitation in the United States in 1946 as to how to deal with these confiscated war paintings: should the paintings be mere propaganda glorifying the war, then they could be destroyed; however if they were art works, by law they should be preserved. A political settlement over this conflict was reached in December 1947, when the US intelligence agency acknowledged the artistic value of the Japanese war paintings.

This work reproduces the Japanese War Art Exhibition which was held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum in the summer of 1946, based on the actual dimensions of the works. The United States military held this exhibition for occupying forces personnel, at a time when the evaluation of the confiscated war paintings was not yet determined. However, the actual collection of war paintings is not present. The paintings were for a long time taboo in the defeated Japan, then stored at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo in the form of a permanent loan from the United States. Instead, close-up images and caption information regarding the paintings provide just an indication of what kind of scenes were made into art. The full-scale “paintings” were created from an enormous amount of material discarded after transportation of displayed artworks and from exhibitions, and recall also the hegemony of the US government in internationally promoting paintings of abstract expressionism as a weapon of the liberal powers during the Cold War. (The Japanese War Art, 2022)

---------------------------------

From that point of view, the patriotic aesthetic system of Vladimir Medinsky, who commis-sioned Salavat Shcherbakov’s military sculpture “Bronze Statue of Grand Duke Vladimir”, set up in Moscow after the annexation of Crimea, is also of interest to me. Medinsky said, “Facts don’t mean much by themselves. Facts exist only within conceptual frameworks. Everything starts not with facts but with interpretations. If you love your country, your people. The history you write will always be positive. Always!” It is clear that the expansion of a history (narrative) created by patriotic passion into a dream to fill a “blank future” is a political technique that is shifting to the right not only in Russia but also in other parts of the world.

GE: Do you have any hopes related to the effectiveness of your work and attempts to look at yourself from the other side? How can art work at critical moments in history?

HF: My art is powerless in the real world where “usefulness” is required. However, the long history of art tells us that catastrophes such as wars and disasters not only physically destroy space, but also destroy the “time” that has been flowing steadily. Art has an abstract and real-istic task of repairing the “time” that has shattered into pieces.

GE: What could you say in support of those who are trying to endure mentally and physically during this difficult time?

HF: I don’t know anything, so I have to refrain from “saying” something. But all types of sup-port begin with "listening” to the voices of people in distress.

—-

Sign of the Times:

— Sign of the Times # 1. History and disposal container by Yoshinori Niwa

— Sign of the Times # 2. The Trajectory of the Family Past by Aisuke Kondo

— Sign of the Times # 3. Pointing at the history by Kota Takeuchi

— Sign of the Times # 4. Fragile gift by Jun Kitazawa