A conversation between writer Tatsiana Zamirovskaya and curator Aleksandr Zimenko

From Issue 4—General Public — Summer 2020 (Archive)

Translated by Anastasia Kolas (Русский текст ниже)

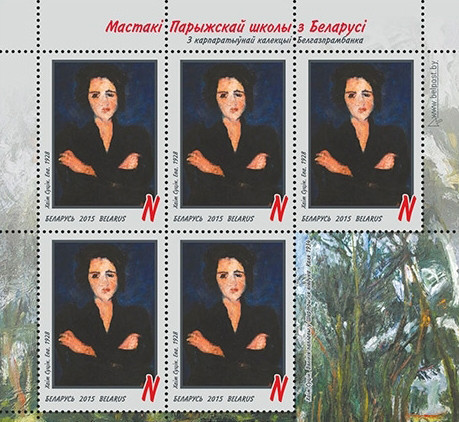

Editor: To cheer myself up during the Nth weekend of protests in Belarus, I am scrolling through the site dedicated to Belarusian protest posters and ‘folk’ art, and notice a recurring image of a painting. I initially take it for one of the many trending contemporary revivals of -isms of the early 20th centuries, but the connection to protest context remained to me, opaque. If you, like me, don’t regularly read Bloomberg news, who have been, I have to say, ahead of the curve of many western publications to provide an in-depth coverage on the subject of Belarus, you may have missed the exposé detailing the story of an unlikely revolutionary icon: “Eve” by Paris School painter Chaim Soutine.

The painting, acquired 6 years ago by Belgazprombank Corporate Collection, formerly headed by now-imprisoned presidential hopeful Viktor Babariko, has been promoted by the corporate owners as a new symbol of Renaissance in Belarusian culture long before the uprisal. From 2011 onwards, the Bank, under the initiative of Viktor Babarkio, has been working on returning key historical works of art to the territory of Belarus. It is important to point out that the layers of entities involved in the organization are somewhat slippery: it is never clear, at least to me, who is genuinely interested in art and culture, and who is merely strategizing. After all, Belgazprombank, is a commercial bank based in Belarus, that’s a direct affiliate of Russian Gazprom, the shady oligarch natural gas monopoly with a tangled and complicated history. My trust, in financial and in Russian organizations is, quite predictably, very low.

Highlighting the conjunction of art-history, geopolitics, revolutionary fervor and neoliberal corporatization of culture, below is a conversation between writer Tatsiana Zamirovskaya, based in New York, and Aleksandr Zimenko, the curator of above mentioned Belgazprombank collection, based in Minsk. Aleksandr has spent twelve hours and then four more in “conversation” with authorities, who accuse him and other associates, including arrested Babariko, of a mysterious crime (of allegedly planning to smuggle the purchased and returned paintings from the collection out of the country). Aleksandr had signed a non-disclosure agreement (which he’d not been given to read, as customary with all arrested during this and in the previous years of the regime). Considering the current climate we are respectfully by-passing anything directly related to the accusations. The omission, nevertheless, does not obfuscate but counterintuitively, helps, to get a fuller picture of the current events in Belarus.

Tatsiana Zamirovskaya: For me, that moment, when the paintings were arrested (that’s how I described it to myself, as 'arrest of the art'), was when I felt something breakdown. At that moment, I had determined for myself that perhaps, in current Belarusian reality, the protests would have to be implemented and formed, as art — due to repressions, and due to stifled communication channels and restricted circumstances. But it so happened that shortly thereafter, art itself became a symbol of protest, too. How did the transformation of Chaim Soutine’s painting "Eve" unfold?

Aleksandr Zimenko: Currently on show, as part of a jubilee exhibition at the Palace of Art (ed: Palatz, Minsk), are several paintings by Ales Marochkin, that were previously banned because they show bchb* flag. The paintings were made back in the 80s. That is to say, that Belarus did historically have these attempts to find point of contact with the viewer, who could not connect to these political topics openly through other spheres of public activity at the time. So today, art continues to do what’s already been started during the post-perestroika period, when artists were among the first to raise questions of that new society’s self-identification. And no matter how trivial it may sound when I say that “tragedies and catastrophes pass through the heart of an artist or a poet”, it feels, in this case, to be true. And, to clarify, I mean to say that we are talking here about a specific creative person, not just someone with a diploma from an institution, who has technical or academic knowledge and skills. I mean a person who reacts — and reacts acutely. And again, no matter how hackneyed the statement may ring, to a large extent this kind of person, I think, feels strongly precisely because they don’t live in a world of 9 to 5, of taking care of their mortgage or credit, but rather they live in a world of their own, devised according to their own rules. And when this personal world encounters tragic and cruel events of the larger world around them, it inevitably reverberates strongly, with a vivid response.

More so, I want to stress here, that all crisis situations tend to turn complex rhetoric into a set of binaries. When the images of "Eve" painting or, let’s say, portraits of Che Guevera, or Maria Kolesnikova appear on T-shirts, it’s not about that specific painting, or a person’s history. It is about the symbolic power of a sign during the crisis. As we can hear in the now popular in Belarus phrase: "Louder than the voices of our friends, we will hear the silence", the crisis turns everything into a choice. Yes or no. With us or against us. This has to do with a desire to idealize certain figures, because an everyday observer as such, doesn’t think about the strengths or weaknesses, context, history or nuances of the image, whether that’s Eve, Che Guevara or Maria Kolesnikova. These images carry a symbol of hope.

And, summarizing this long answer: at the moment, through these images, we continue to develop that very question, of Belarusian self-identification, which has not yet found an unequivocal answer.

TZ: There is also another side of this binary oversimplification, where the history of protest and self-identification is viewed on the outside, in this case, outside of the country. As a person who for the past 5 years has lived in New York, I feel that as Belarusians, we have a complicated narrative to our revolution that doesn’t fit a module, does not sell as if a script by Joseph Campbell, in the vein of "The Thousand Hero". Much of the context is simply not clear to the outside eye. But something like — “the dictator arrested the paintings” — that kind of thing is clear to my American friends, can resonate. There is an element of Kafka to it.

AZ: It’s like whipping the sea, because a raft sank.

TZ: Exactly. But it’s difficult to tell the story of the three women who have been at the forefront of the recent protests, because their story falls out of the patriarchal archetypes of 'evil dictator vs. the liberator'. How can I explain that one of the three leaders is the wife of someone who didn’t even become a presidential candidate (ed: Tsepkalo, whose signatures were rejected by the Central Election Commission), the second person was on staff of the arrested candidate hopeful, who never had a chance to register (Kolesnikova worked as Babariko’s staff), and the third is wife of the popular blogger-candidate (Tikhanovsky), who was also arrested before he could register. This story begins to fall apart because these are women who were nearly accidentally, or due to circumstance, pushed onto the center stage and were not meant to be the title characters themselves…

AZ: …because the image you are describing is not about the confrontation between heroes as individuals, in this case, the image represents, accurately, the confrontation between the masses and one individual.

TZ: Right, and that’s another important point to discuss, but before we turn to that, I’d like to stay for a moment longer with the role of women in Belarusian protests, rewinding to the time when Chaim Sutin’s painting "Eve" becomes a protest symbol. That moment, I think, can be described as almost prescient to the women’s central role in the current uprising, even before the arrival of the trio we just discussed. How did the process that brought "Eve" to her current place in history unfold?

AZ: I think of it as more of an objective process, than a mysterious flow from one event to another. Why "Eve"? — there’s been a lot of discussion where we’ve been trying to analyze its transition to a symbolic level. And in the end I think it’s a shining examples that we live in, not merely post-industrial, but already in what can be described as, the information society. The initial notoriety of the painting is the result of a sincere attempt to promote our collection under the image of this, possibly incomprehensible, but elegant work. It was not the main concern, for my colleagues and I, that the public must love this work of art. Rather, we wanted to draw attention to its place in our, and in the world, history, and to the fact that this painting was now in the collection of Belgazprombank (Art-Belarus), and that this painting is an important historical work of art in general. By now it’s been six years from the moment of its purchase, and since the time when we began to intentionally distribute its image.

On the other hand, I think the reason for “Eve’s” rise to fame in this other context, is also related to the work itself, the very posture of Eve. The collection that has been ‘arrested’ has many other works that could have potentially carried revolutionary symbolism. There’s, for example, "Portrait of Tomas Zan", by Valentin Vankovich, who painted a portrait of his friend and fellow student at Vilnius University. At the time they were both members of the Filaret and Filomat secret societies. These secret societies appeared as a response to the policy of Russification on the territory of former Rzeczpospolita, after its partition. These secret societies fought for preservation of national language and culture. Another example of revolutionary potency could have been "In the prison cell" by Nikodim Silvanovich. Although this work was still painted in the style of classicism, one can already notice the beginning of a paradigm shift that was about to take place in Fine Arts of the Russian Empire. The prisoner shown here is no longer a Christian, or antique hero, but a modern artist. And by the way in which this person is depicted in the painting, one can understand how the author relates to the fact of his captivity. The depicted artist has an open face, his head is raised high — suggesting that this person, while imprisoned, is not broken. And equally legible is the author’s condemnation of his captivity.

But in the end, it is this female image in Soutine’s painting "Eve" that resonated with the contemporary discourse, interpreted by many as a pose of resistance despite the fact that the pose is what we would call, closed, and her hands are crossed at her chest. This is the power of Soutin as an artist: it’s not just a beautiful female figure or a pleasant image, but the image of a person with a strong character. And although it’s an anonymous portrait, there is a very distinct presence of a powerful persona, in it. The first memes about the painting were: she’s led by the riot police, or she is behind bars, but invariably because of her posture, she appears in all, disobedient. This, again speaks to the archetypes and falls in line with the myth of Belarus as a country of well-documented guerrilla ethos, a (partizan) republic that’s been occupied many times in its history, but each time liberated itself from the occupant forces. And of course, only people wearing tin hats can believe that there is an influence from the West, or from anywhere else. There are no puppeteers here. I would like to emphasize: you’d have to be an incredibly adept political operator, to plan this whole sequence of events to the extent that it has happened — first, this painting, then the trio, then, the women’s march… It’s really obvious that the painting is just a strong image, and the rest is clearly a self-developing situation too. And the same can be said about the three individuals who chose to lead the country to the elections and after: now they too, have turned into images that are no longer even related to the specific people that they depict, but are symbols in their own right, of a general societal mood.

TZ: I agree, it would have been impossible for anyone to have planned the current protest phenomena in such detail. Instead, I tend to call it the Belarusian singularity, the black swan: the fact that it all bubbled up across dispersed locations at the same time, and that it happened now**. To close the subject of "Eve" as an archetype: to me, the painting seems to symbolize a kind of a return. The painting is from the collection of recently returned to Belarus, many of which were in turn painted by artists who left for various reasons, but, let’s say, united by a certain impossibility of self-realization in this country. And, the artists continue to leave Belarus because of that same persisting impossibility of self-expression and self-actualization.

AZ: Again, here I would not draw a direct parallel between the last century and what is happening now. Let’s not forget: none of those who painted these paintings could have predicted that there would be the First and, let alone, the Second World War. The territory of Belarus during that period was always in the center of military operations, and that’s the reason why many people ended up elsewhere. Besides that, art centers always existed — such megapolises as Paris-Berlin-New York, are just most recent centers where art is valued, exchanged and supported. Or as another example: historically, painters often went to Italy just to see the production of paints themselves, and the colors up close, which were produced in that location only because of the presence of natural materials necessary for the paint production. As to the artists who left in the last 30 years, or are leaving at the moment, it’s a different situation. At this point, I think, it doesn’t matter where they go, geography can no longer fundamentally change the already established personality of a person, nor their roots. And, giving that we live in a post-industrial information society, I think we have already moved to another level, where the origin doesn’t define the artist as much as it used to, where the subtleties of their spiritual reflection may have not been lost to a specific locale, because of cultural differences. I am skeptical about this narrative. I believe that today an artist of a significant talent can be legible in any society. We are no longer existing in isolated vessels of distinct cultures, where we are simply exchanging goods, or trade books, and so on. Yes, fashion comes and goes, sometimes Iranian artists are popular, sometimes Chinese, but that’s market: that’s a different set of concerns.

TZ: Thinking about the commercial side of the intersection of protest and art: one of my friends told me, after the protests began, that she’d written to Nike to suggest customized sneakers with symbols of independent Belarus, in support of the protestors. She basically proposed to this corporation to design sneakers "good for running away from OMON***". Here, the protest becomes both an aesthetic and a commercial, marketing, sphere.

AZ: This is related to a strange specificity of the Belarusian protest, which reminds me of the collapse of Czechoslovakia. It’s not an image of a burning tire or a hammer cocktail like in Ukraine during Maidan, it’s not the Swan Lake and tanks like during the collapse of the Soviet Union in Moscow, it’s not the wall in Berlin: it’s people carefully taking off their shoes during the protest to stand on a bench during the solidarity action in the square. What’s more, atrocities and flash-grenades are, sadly, no longer distinct, as images, across the many countries where they are used, in terms of tactics. This could be an image taken anywhere, from Seattle to Hong Kong. But when white boxes of Adidas shoes are made to deliberately alternate with the red boxes of some other brand in the windows of a shoe store to mimic a flag, it looks impressive. Similarly, at this point in history, the riot police uniform seen in a contemporary documentary image or on a film-set, can’t be distinguished from one another, their uniform looks more or less the same all over the world. But the image of the protester — that looks quite different. In this case, I think, it presents a positive image, both to the Belarusians themself, and to the outside. This image doesn’t show people who’d set something on fire, or who vandalize property. Here, we see people who clean up garbage after a day of demonstrations, and who take off their shoes to get up on a bench.

TZ: But there is still this observable archetype battle between two aesthetics: an armed policeman, or a riot police officer, up against the aesthetics of the protesters…

AZ: …You can consider this example as a kind of imitation of antiquity. The OMON, uses the tactics of the Roman Empire legions: the formations, the shields and so on. And who was the Roman legion fighting against? Against the barbarians! The barbarians throw stones, shout, and against that backdrop, the legion appears to be a symbol of order. Of course, this is the same symbol that kills, but it also develops. It invades and captures, but also brings with it roads, aqueducts, money, medicine. Following that same narrative, the Belarusian propaganda tries to continue to present itself as order against the chaos of protests. Because, historically, precisely by behaving violently, many protesters do often fall under this archetype. The Romans, too, were certain that they represented civilization, and that they were bringing order. Today, the spear becomes a police truncheon, and the shield has not even changed. But in Belarus this narrative falls apart when "barbarians", that come out against the so-called ‘legion’ of order, are completely peaceful, and present absolutely no violent behavior to the police.

TZ: I think, it’s a good moment to talk about the evolution of performance in Belarus, since the start of activity of someone like Ales Pushkin, who brought a cart of manure to the president’s residence entrance, piercing the president’s portrait atop it, with a pitchfork… In terms of performance, I always think of Belarus as quite advanced in that art-form.We’ve held the international festival 'Novinki' here since the late 90s, so it seems to me that the Belarusian spectator is very welcoming to this form of art, and performance has been historically, and continues to be today, very active. In a sense, even someone like Nina Baginskaya, with her "I’m just going for a walk", is in some sense performing, a kind of life-long performance of endurance, of both body and spirit. And, at the same time, she’s also testing the endurance of the law enforcement.

AZ: This is a moment of a metamorphosis, where instead of the actions of individual performers, all of us, here in Belarus, live inside — a one single big 'happening'. What’s taking place now, is no longer a performance, because performance would imply a presence of an onlooker. Even in the case of Ales Pushkin — everyone was looking at him. Someone arrested him, someone else said "bravo", someone else thought to themselves “bravo”, but said nothing out loud… And now, when so many people actively go out daily, weekly, and participate, it’s already a ‘happening’. One can draw parallels with the main characteristic of this revolution and its decentralized horizontal organization. We don’t have a certain single center, or a leader, and everyone decides for themselves whether to go to the protest or not, and when to do it. And we can say that the law enforcement agencies, in a way, are also participating in this, when, for example, they use water cannons to disperse spontaneous circle dancing in Brest. This is a typical sign of a ‘happening’ that operates not as an observed performance, but as a collective activity with a single purpose, where there are even certain rules, there is timing for everything, and at the same time, it’s a kind of performance that happens en masse.

*Abbreviation.: бчб — white-red-white flag, in Belarusian.

**For a deeper background on (not at all) sudden uprisal in Belarus, please read Nacre’s last year essay, contributed by the curator Ilona Dergach

***Belarusian special forces.

__

Архаичные архетипы: Татьяна Замировская беседует с Александром Зименко

От редактора: Чтобы поднять себе настроение во время N-ых протестных выходных в Беларуси, я захожу на Телеграм и дивлюсь фольклором и постерами, и в какой-то момент замечаю повторяющееся изображение некой картины. Её я изначально воспринимаю как одно из многих современных возрождений -измов начала 20-го веков. Связь с контекстом протеста остается для меня туманной. Если вы, как и я, не живете в Беларуси и не читаете регулярно новости Bloomberg, вы вероятно также, пропустили репортаж с подробным изложением истории новой революционной иконы: о картине "Ева" Хаима Сутина, художника из Парижской Школы.

Картина, приобретенная 6 лет назад Корпоративной коллекцией "Белгазпромбанка", которую ранее возглавлял находящийся в заключении Виктор Бабарико, ещё задолго до восстания продвигалась корпоративными владельцами как новый символ Ренессанса в Беларуской культуре. С 2011 года Банк по инициативе Виктора Бабарико работал над возвращением ключевых исторических произведений искусства на территорию Беларуси. Важно отметить, что игроки, участвующие в организации, несколько сомнительны: никогда не понятно, по крайней мере мне, кто действительно интересуется искусством и культурой, а кто просто разрабатывает им нужную стратегию. Ведь "Белгазпромбанк" — это российский коммерческий банк, имеющий базу в Беларуси. Мое доверие как и к любым финансовым, так и к Российским организациям, по понятным причинам (я живу в этом мире), низкое.

История искусства, геополитика, революционное вдохновения и неолиберальной корпоратизации культуры, пересекаются ниже, в беседе писательницы Татьяны Замировской, живущей в Нью-Йорке, и Александра Зименко, куратора вышеупомянутой коллекции "Белгазпромбанка", в Минске. Александр провел двенадцать, а затем еще четыре, часов в "общении" с властями, которые обвиняют его и других соратников, в том числе арестованного Бабарико, в загадочном преступлении (в том, что он якобы планировал вывезти за пределы страны купленные и возвращенные из коллекции картины). Александр подписал соглашение о неразглашении (которое ему не дали прочитать, как это принято со всеми арестованными, и сейчас и в предыдущие годы режима), поэтому, в нынешних условиях мы с уважением пропускаем в беседе ниже все то, что связано с обвинениями.

ТЗ: Момент, когда произошел арест картин, а я это именно так себе описала — как арест искусства, для меня был моментом какого-то разлома. И именно тогда я определила для себя, что в Беларуской реальности протесты вынуждены осуществляться и формироваться как искусство. Именно из-за репрессий, из-за стесненности обстоятельств, но при этом получилось и так, что само искусство также стало символом протеста. Как это случилось с картиной “Ева”? Размышлял ли ты об этом и как ты видишь данную ситуацию?

АЗ: В Дворце Искусства (ред: Палац, Минск) сегодня проходит юбилейная выставка, в которую включены картины Алеся Марочкина, которых раньше запрещали именно потому, что в них показывается бчб* это картины, которые он делал еще в 80-х. То есть, в Беларуси исторически уже были эти попытки найти точки соприкосновения со зрителем, которого беспокоят темы, которые этот зритель не мог найти отображаемыми (открыто) в других сферах человеческой деятельности. Изобразительное искусство сейчас продолжает то, что было заложено в послеперестроечный период, когда именно художники были одними из первых, кто начал задаваться вопросами построения самоидентификации нового общества. И как бы это банально и избито не звучало, что трагедии и катастрофы проходят через сердце художника или поэта, это действительно так. Если мы говорим о настоящей творческой личности, а не просто о человеке, у которого есть диплом, подтверждающий что он какое-то время провел в том или ином учебном заведении, владеет какими-то техническими или академическими знаниями и навыками, то это скорее человек, который остро реагирует. И как бы опять же это патетично не звучало, в большой степени такой человек чувствует это настолько сильно, потому что он не живет в мире, где ходят с 9 до 6 на работу, заботятся об ипотеке или кредите, а живет в своем мире, по своим правилам. И когда этот мир сталкивается с трагическими, жестоким событиями, то это производит действительно сильную ответную реакцию.

Развивая эту мысль, в то же время, кризисные ситуации все превращают в бинарность. То есть, когда изображения живописи Ева или портреты Че Гевера или Марии Колесниковой появляются на майках — это уже не про конкретную живопись или человека с его историей. Это про символическую силу знака во время кризиса. Как произносится в популярной сейчас фразе: “громче, чем голоса наших друзей, мы услышим молчание”, кризис превращает все в выбор. Да или нет. С нами или против. В этом есть стремление идеализировать те или иные фигуры, потому что повседневный наблюдатель в такой момент не задумывается о сильных/слабых сторонах, контексте, истории или нюансах изображения как и Евы, так и Че Гевары, или Марии Колесниковой. Эти изображения — символ надежды.

И, обобщая этот длинный ответ: на данный момент через данные изображения у нас продолжается развитие вопроса Беларуской самоидентификации, который до сих пор по сути не нашел однозначного ответа.

ТЗ: Есть также еще другая сторона этой бинарности или упрощения, когда история протеста и самоидентификации сталкивается с перспективой извне страны. То есть как человек проживший уже 5 лет в Нью Йорке, я чувствую что у нас сложный нарратив нашей революции, не продается как сценарий по Джозефу Кэмпбеллу, как в “Тысячеликом герое”. Многое из контекста просто не понятно, но вот такие вещи как — диктатор арестовал картины — это понятно моим Американским друзьям, это их впечатляет. В этом есть элемент Кафки.

АЗ: Это как высечь море, потому что утонул плот.

ТЗ: Да, но вот историю трех женщин рассказать сложно, потому что она выпадает из патриархального архетипа героев: злой диктатор/добрый освободитель. Как объяснить, что одна из трех лидеров — жена того, кто не стал даже кандидатом в президенты (ред: Цепкало, подписи за которого были забракованы Центризбиркомом), вторая — работница штаба того, кто был арестован и тоже кандидатом не стал (Колесникова работала на штаб Бабарико), а третья — жена самого популярного блогера-кандидата (Тихановские), тоже арестованного прежде, чем он смог зарегистрироваться. Эта история начинает рассыпаться потому что это женщины заместительницы, а не сами героини…

АЗ: …потому что эти три образа говорят о противостоянии не героических индивидуумов, в этом случае, а о противостоянии масс, многих людей, против одного человека.

ТЗ: Да, что тоже очень важно обсудить, но прежде чем мы двинемся дальше, я бы хотела продолжить тему женского облика в Беларуских протестах, немного перемотав к тому моменту когда картина Хаима Сутина "Ева" стала символом протеста. Это можно описать как момент предсказания того, что настоящие события станут революцией, где женщины будут играть центральную роль даже до возникновения этого трио. Как развернулся процесс, в результате которого картина “Ева” получила такое место в истории?

АЗ: Мне кажется, эти процессы скорее объективны, чем основаны на том, что одно вытекает из другого. Почему “Ева” — много было дискуссий, попыток проанализировать её переход на символический уровень, и это действительно хороший вопрос. Я думаю что это один из ярких примеров того, что мы живем не просто в постиндустриальном, а в информационном обществе. Изначально это была искренне попытка многих людей продвинуть нашу коллекцию под изображением этой, может быть непонятной, но шикарной работы. Для моих коллег и для меня не было главным и обязательным, чтобы работа нравилась, мы скорее хотели привлечь внимание к тому, что она есть в нашей истории, и теперь в коллекции Арт-Беларусь, и что это важная работа. С момента ее покупки будет уже сейчас шесть лет, мы намеренно распространяли это изображение. Это с одной стороны.

С другой, мне кажется, это также связано с самим произведением, самой позой Евы. В коллекции, которую арестовали, есть, например, и другие работы. В смысле потенциального революционного символизма имеются, например, “Портрет Томаша Зана”, Валентина Ваньковича, который написал портрет своего друга и сокурсника по Виленского университету. Они оба входили в тайные общества Филаретов и Филоматов. Эти тайные общества появились как ответ на политику русификации земель Речи Посполитой после её раздела. Боролись за сохранение национального языка и культуры.

Или есть в коллекции работа “В Темнице” Никодима Сильвановича. Хоть работа и выполнена в стиле классицизма, в ней уже можно увидеть смену парадигмы в изобразительном искусстве в Российской Империи. На ней в темнице сидит уже не ранний христианин, или античный герой, а современник художника. Причём по тому, как изображён этот человек, можно понять, как автор относится к факту его пленения. Это не душегуб или бандит, у изображенного художника открытое лицо, поднятая голова — все говорит о том, что человек даже находясь в заточении не сломлен. И автор осуждает его пленение.

Но вот этот женский образ живописи “Ева”, несмотря на то, что поза закрытая и у нее скрещены руки, она все равно многими была интерпретирована как поза непокорения. В этом и есть сила Сутина как художника: это не просто прекрасная дама или приятное изображение, а образ человека с сильным характером. Пусть это и анонимный портрет, но в нем есть присутствие сильного человека. То есть первые мемы про нее были, что ее ОМОНовцы ведут, или она за решеткой, но неизменно из-за её позы, она выглядит непокоренной. Это, опять же говоря о архетипах, ложится на миф страны как партизанской республики, которая много раз за свою историю была оккупирована, но каждый раз добивалась освобождения от оккупантов. Ну и конечно, только люди в алюминиевых шапочках могут верить, что здесь есть влияние с Запада или еще откуда-нибудь. Кукловодов здесь нет. Мне бы хотелось подчеркнуть: надо быть мега политологом-манипулятором чтобы так всё запланировать — вот эта живопись, распространяем и апробируем её для протеста, раз. А теперь мы девушек на улице запускаем, два… Это просто действительно сильный образ, и действительно объективно развивающаяся ситуация. И то же самое можно сказать и о трёх отдельных личностях, сделавших выбор вести страну к выборам: сейчас они тоже превратились в образы, уже даже не связанные с конкретными людьми.

ТЗ: Согласна, что такие явления невозможно прогнозировать, я скорее это называю беларуской сингулярностью, черным лебедем: то, что одновременно стало проявляться в разных местах, и что это произошло именно сейчас. Чтобы завершить тему “Евы” как архетипа: она, мне кажется, символизирует момент возвращения. То есть, она из серии картин, недавно возвращенных в Беларусь, написанных в свое время художниками, которые уехали, по разным причинам, но, скажем так, объединенные некоторой невозможностью самореализации в этой стране. Сейчас художники тоже покидают Беларусь из-за невозможности самовыражения и самореализации.

АЗ: Я опять же здесь бы не проводил прямую параллель между прошлым столетием и тем, что происходит сейчас. Не будем забывать: никто из тех, кто писал эти картины, не мог предсказать, что будет Первая, да еще и Вторая Мировая Война. Территория Беларуси в те времена всегда находилась в центре военных действий, и поэтому люди и уезжали. Ну и центры искусства существовали давно, такие мегаполисы, как Париж-Берлин-Нью Йорк, где искусство ценилось, обменивалось и поддерживалось. Ну или как другой пример: исторически, живописцы часто ездили в Италию просто для того, чтобы увидеть производство самих красок и эти цвета, которые производились только там из-за наличия натуральных природных материалов. И художники, которые уехали в последние 30 лет, или уезжают отсюда на данный момент, это уже другое. Теперь не важно куда они уезжают — география не может в корне изменить устоявшуюся личность. И опять же, живя в постиндустриальном информационном обществе, я думаю мы уже перешли на другой уровень, где происхождение не настолько определяет художника, как это было раньше, когда его тонкие духовные размышления могли не понять в специфическом местном обществе из-за культурной разницы. Я скептически отношусь к этому, мне кажется, достаточно талантливый художник будет восприниматься в любом обществе. Мы не уже не находимся в изолированных сосудах культур, где мы просто обмениваемся или торгуем книгами и так далее. Да, мода приходит и уходит, то иранские художники популярны, то китайские, но это рынок, это другое.

ТЗ: Думая про коммерческую сторону пересечения протеста и искусства: одна из моих знакомых написала после начала протестов в Найк, чтобы предложить кастомизировать кеды с символикой независимой Беларуси, в поддержку протестующих женщин. То есть дизайн кедов “в которых хорошо убегать от ОМОНа”. Здесь протест становится эстетической и коммерческой сферой.

АЗ: Это странная специфика белорусского протеста, который больше напоминает распад Чехословакии. Это не горящая шина и не коктейль молотова, как в Украине, это не Лебединое Озеро и танки, как во время распада Советского Союза в Москве, это не стена в Берлине, это люди снимающие аккуратно обувь во время протеста, чтобы встать на скамейку во время акции на площади. Ну и зверства и свето-шумовые гранаты как изображения в смысле тактики не отличаются от других стран: к сожалению, это может быть везде, от Сиэтла до Гонконга. А бчб, когда в окнах обувного магазина белые коробки Адидас намеренно чередуется с красными еще какой-то марки, это впечатляет. Форму наряда милиции или документальное изображение страны в кино, на данный момент истории, невозможно отличить друг от друга, они всегда более-менее одинаковые. А вот образ протестующего — это выглядит совершенно по-разному, и в данном случае, я считаю, является положительным примером, как для самой Беларуси, так и для взгляда извне. Это изображение не показывает людей, которые что-то поджигают или разбивают. Здесь мы видим людей, которые убирают за собой мусор, и без обуви встают на скамейку.

ТЗ: Но есть всё же битва двух эстетик: вооруженного полицейского или ОМОНовца, против эстетики протестующих…

АЗ: …Можно рассмотреть этот пример через имитацию античности. ОМОН, как и многие другие силовики, использует тактику легионов Римской империи, построениещитов и так далее. Против кого Римский легион сражался? Против варваров! Варвары в них что-то кидают, кричат нечленораздельно, а легион — это порядок. Он, конечно, убивает, но также развивает. Вторгается и захватывает, но при этом несет с собой дороги, термы, деньги, медицину. Точно так же пропаганда пытается продолжать представлять себя протестующим. Потому что исторически протестующие часто попадают под этот архетип, ведя себя таким образом. Римляне тоже были уверены, что они представляли цивилизацию, что они все в порядок приводят. Ну и теперь это транслируется в резиновую дубинку, а щит даже не поменялся. Но в Беларуси этот подход ломается, когда против легиона выходят “варвары” которые ничего не громят.

ТЗ: Как раз хороший момент поговорить про эволюцию перформанса в Беларуси со времени Алеся Пушкина, когда он привозил к резиденции президента навоз и протыкал его вилами… Беларусь в смысле перформанса мне всегда казалась передовой страной, у нас также проходил интернациональный фестиваль Новинки, начиная с конца 90-х. Мне кажется что беларуский зритель очень натренирован, и эта форма искусства исторически и каждодневно активно работает… В каком-то смысле даже та же Нина Багинская, с её “Я гуляю“, это в каком-то смысле перформанс, даже lifetime-performance, в котором она осуществляет перформанс на выносливость тела и духа. И также тест на выносливость силовиков.

АЗ: На данный момент мы находимся в периоде определенной трансформации, где вместо действий отдельных перформеров, мы теперь — все — живем в одном большом хэппенинге. Это уже не перформанс, потому что перформанс это когда кто-то стоит и смотрит. Тот же Алесь Пушкин — на него все смотрели. Кто-то его сажал, кто-то говорил “молодец”, кто-то про себя думал, что молодец, и вслух ничего не говорил… А теперь, когда такое количество людей выходят и участвуют, это уже хэппенинг. Можно провести параллели с самой тенденцией этой революции, где все организуется горизонтально. У нас нет определенного единого центра или лидера, и каждый решает сам, ходить на протест или не ходить, и когда что делать. И можно сказать, что силовые органы тоже в этом участвуют, например, разгоняя спонтанные хороводы водометами в Бресте. Это типичный хэппенинг: не просто наблюдение, а активность в едином процессе, где есть свои правила, есть свое время, и при этом — массовость.

*сокр.: бело-красно-белый флаг по беларуски