EXHIBITION – A WESTERN RITUAL. Art historian Dorothea von Hantelmann, on her research and upcoming book

From Issue 5—Rose of Venus— Summer 2023 (Archive), co-edited with Hanna Horn (The text has been condensed and edited for clarity and flow)

Anastasia Kolas: I’d like to begin by asking you to tell us about yourself and your research, in your own words, perhaps starting from your initial interest in museums, to how you came to think about exhibitions as a ritual in your research?

Dorothea von Hantelmann: I’m a trained art historian, studied art history and gradually developed interest in 20th-21st century art. I wrote my master thesis on Marcel Broodthaers and his imaginary museum. He, and later Daniel Buren, belonged to the first generation of institutional critique artists from the late 1960s and 1970s. However, their position was not only informed by the spirit of the critique of the institutions, since both of these artists also loved museums, but also by the parameters that went into consideration when making and interacting with an artwork. So after studying their work and then completing my PhD, it was while working as a researcher at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, I had my, let’s say, crisis moment in relation to art: working with art, and loss of interest in visual art. So I began to look elsewhere and became interested in dance and theater. I also spent a lot of time with the artists around me. My work and research was very much shaped by this experience — by staying very close to the practice of art, rather than having an academic distance. I think my interest in what I would now call “the exhibition format” really began here: in observing that artists took the entire exhibition situation into account, because they realized that it informs the experience of their work and becomes part of the work regardless of whether they are aware and want this, or not. Already in the 1990s I became very interested in the work of artists that came from visual art, but really worked on and with the exhibition format, such as e.g. Pierre Huyghe, Philippe Parreno and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster — the so-called “relational aesthetics” generation. I was very influenced by them, and we are more or less of the same age, so these are my references. I’ve written about some of them and their artistic development influenced mine, as an art historian.

AK: How did you come to connect these relational aesthetics practices to what you describe as “an exhibition as a ritual” today?

DvH: I supposed this would be a sort of second part of the “how it all began” question. I’ll start to answer it here from a slightly different angle: I come from a rather bourgeois background, so museums had been a part of my education. I always liked museums, they seemed to me like places of refined sensitivity and beauty, which I enjoyed without necessarily understanding much of it. It was just part of my culture, part of my upbringing. So in a way I didn’t question it, exactly because it was an inherent part of who I was and how I was educated as a young person. This changed over time, first of all because I became interested in other forms of art, like dance and theater as I mentioned, but also because I was reading, traveling and learning about exhibition and museum history. I wanted to know why museums and exhibitions became so popular and so wide-spread throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, to a point where they were imported by other cultures. Up to the mid-20th century, there were only two major periodic art exhibitions: Venice and Sao Paulo — whereas today there are over 200 worldwide. In the early 2000s there was a global museum boom: many new museums were about to open in China, the Louvre Abu Dhabi was built, and numerous Biennials and Triennials were founded all over the world. Why was this happening? What is it that made this format so important, and so attractive? That was a question that really motivated my research.

And I understood that to answer these questions we’d have to understand what made the format of the exhibition attractive in Western Europe in the first place. I wanted to study how this, let’s say, initially relatively unspectacular format had flourished and spread widely through the course of modernity. But then I also wanted to understand how and why in the last 20 years, there emerged an increasing fatigue with this format.

I worked in Kassel for a while, I held a position of documenta professorship there, and during this time read a lot about the history of documenta. It struck me that since Catherine David’s documenta 10 in 1997, most curators of documenta — which is considered the most prestigious, and the most important contemporary art exhibition — have accepted the invitation to curate it, while saying they didn’t really want to curate an exhibition. They called it differently and found different ways around it. Catherine David called it manifestation culturelle and initiated the “100 days 100 guests” events; Okwui Enwezor initiated Documenta 11 not with the exhibition, but by creating platforms, which were more discursive, and included theoretical conferences in different places in the world; Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev also displaced the exhibition and at the same time transformed it into a kind a of festival. I was curious to find out why the exhibition format seemed increasingly too limited to present art in a way that seemed contemporary and relevant.

A jump forward to my current situation, as a professor at Bard College Berlin, where I often take my students to see exhibitions. Today, I sometimes get shrugs in response when, e.g., I propose to go to Hamburger Bahnhof. “It’s so 20th century”, they say. At the beginning I was a little irritated by their reaction. But I found myself thinking they also have a point here. We have students from over 60 countries, speaking 40 languages on campus, from very different cultural backgrounds. These institutions are not as ‘naturally relevant’ for them as they had been for me. So these are all different aspects of what changed my perspective on museums and exhibitions. In a way over time my relationship to the format became more and more that of an anthropologist. Generally speaking, one can study museums and exhibitions from two perspectives. As an art historian you basically see them as containers for what art history focuses on: the artworks. The other perspective is to look at them more from the angle of sociology, anthropology, and history. Which is a large and a very heterogeneous field that became more and more interesting to me, especially through the work of authors like Tony Bennett or Carol Duncan. Carol Duncan is the person who introduced the concept of a ritual in relation to museums: she called it a “civilizing ritual”. Both of these authors examined the social and governmental role of the museum, and what Bennett calls the “exhibition complex”.

AK: Related to this, elsewhere you discuss the label in the museums as the very specific format, reflective of a museum being a structure that represents its society: the label highlights individual makers and marks western linear time, while also pointing to cultural accumulation beaconing in the future as an aspirational model. But there is another element of labeling that I wanted to discuss — when the labels begin to describe feelings one should have about the work: when the work is described as foreboding etc. I’ve seen this in many institutions of late. In our initial conversation you also rightly pointed out to me that western canon is in fact a very esoteric kind of knowledge at this point. So presumably these textual instructions reflect a desire to provide context, but often ends up feeling patronizing, or foreclosing. How could institutions work with space, text and also indexing differently without coming across as patronizing or overbearing?

DvH: I think I would start to respond to this by unpacking what I mean by “ritual” in relation to exhibition format. From studying authors like Bennett, Duncan and others, emerged the central question of my research: what does it mean to study museums and exhibitions as specifically modern rituals? For some, this articulation in itself is already a provocation. Because western modern societies have cultivated certain anti-ritualism, and tend to perceive rituals as something archaic, pre-modern and therefore obsolete.

Ritual, in its basic definition, is a moment or a situation when the fundamental principles of a society are acted out. By being acted out, embodied and performed, these otherwise abstract principles or values become manifest. Rituals have two functions: they connect us to something higher, to values that a society considers foundational. It could be something sacred or transcendental, or it could also be a secular value. And then rituals have a horizontal function: they connect the members of a given society to each other. Kneeling in a church is an example. You literally make yourself small before something that is greater than yourself. Over the years a sense of humility is instilled in this way. It’s anchored in people’s minds and bodies, both individually but also collectively. I would argue that, even if we don’t name our rituals as such in a western modern society, it doesn’t mean we don’t have them, nor that we don’t still need them to act out our values. Museums have become one of the places where this happens. Now, the question is — what are these values and how do they become manifest in an exhibition?

The primacy of an individual is one of the foundational tenets of the western modern society: the individual as an entity that votes, that has rights, and so on. In a museum this is cultivated in two ways: by celebrating the individual artist-producer, and by focusing on the individualized experience, the one-on-one encounter of the visitor with the exhibited works. This is in contrast to what happens in a theater play or during a dance performance — both of which are formats of a collective, shared experience. In an exhibition the individual is placed in relation to a material object. This constructs a subject-object relationship that lies at the core of bourgeois culture. Structurally speaking, the object is a material product, not only in relation to a materialist, market-based socio-economic structure, but also as an object that is primarily seen, thereby establishing a certain ‘regime of the senses’ that prioritizes the eye, which, per Georg Simmel, is a modern, and also a distancing way of sensing. While in many other rituals in the history of ritualized gatherings and celebrations, we find people coming together to chant, to dance and to celebrate, here we find other values being formed — namely, critical judgment, reflection — into a highly sublimated, disembodied form of an aesthetic experience. It is a specifically modern ritual in the sense that it cultivates specifically modern values to an audience who, as Carol Duncan put it, were supposed to be ‘civilized’. Meaning this type of ritual teaches us to think and act in a rational, judgment-based way. A ritual inducing other states of consciousness, like trance e.g., would be its opposite. The museum, in contrast, is about understanding and refining yourself in your individuality.

So coming back to your question: museums deal with affect and emotions in a highly rationalized and sublimated way. At this moment in time, society is in a phase of trying out different new modalities, in baby steps. So what you describe, the text that tells you how to feel, is perhaps part of this search for other modalities. As educational departments and pedagogy have gained momentum and become more significant in the context of museums and exhibitions, the wall texts are part of that effort: of reorienting these places and taking them from the 20th century into the present. This means making them more accessible and inclusive, sometimes through trial and error. Much more difficult would be to transform these institutions on a fundamental level, not just through the wall text, but by changing the feel of the place, sensually. The book I’m writing is an attempt to explore the answers to this question.

AK: I’d like to return for a moment to the regime of the senses you mentioned, and link it to what you call in your writing “surrogate gatherings”. You make an example of television when it started, and was an individualized, but also a time and space bound experience across a group of people, or a nation. Technically, today the social media might be an example of a surrogate gathering: it acts on a staggering global scale, uniting people in a temporal capture, and also reflects what you call “holy” — what’s at the center of our society: the image, individual, frame, technology, capital. But you don’t explore the internet as the place of assembly in your work. My understanding is that by insisting on focusing on public spaces and museums instead, you imply that making overemphasis on social media as the best new way of connecting groups of people, is an emphasis in the wrong direction. In other words, it is important to conceive of something entirely different to counter the disembodied relations, alienation of modernity and its tendency towards performative individualism. You suggest that if re-thought, museum and gallery spaces can be that place of change. Though I would say most people don’t really go to museums to connect to strangers, but more to pass the time, meet friends, learn. And, at this point the tendency to jump online is very prevalent, for example we’re speaking online despite being in the same city. In what ways do you think institutions can counter tendencies and habits of an atomized society?

DvH: So, the big achievement of western modernity, seen historically, was to loosen social, epistemological and ontological ties that were experienced as too rigid in feudal, pre-modern and aristocratic societies. With that emerged the ideas of liberalism, individualism, and various other political and social movements. These movements were presumed to be emancipatory, their purpose being to cut these primordial ties and to foster liberation. But the flip side of this process is that we find ourselves in the 21st century, where many people are suffering from being lonely, or as you said, feeling atomized. So we went from strong ties to weak ties, and the latter fails to fulfill people’s social, mental and emotional needs.

Museums are interesting places because in their very basic structure they mirror the basic social structures and mindset of a society. We can read the white cube as a symbolic image of our separated society: it’s an image of separation of nature and culture, separation between people, between objects and the place of their origin — it’s a highly cartesian space, if you like. But the question isn’t how to transform it into its opposite, but how to engage in a process of re-calibration. This means asking: how connected, and how disconnected, how regulated, and how unregulated, with which part of our bodies and senses do we want to encounter art and each other within these places?

AK: I suppose here it might start to feel like a bit of a chicken and egg scenario… I was thinking that if, as you say, museums or exhibitions rituals reflect how that society operates, then does society need to change first, or can the changes emanate from within these institutions?

DvH: That leads to a very interesting question: how do rituals change? And it’s a complicated question, because on the one hand rituals derive their legitimacy from the fact that they transcend the individual, and therefore cannot be modified at will. Their potency lies in the order that precedes the individual and lasts longer than an individual. On the other hand, rituals are not essentially stable. They change along with the changing socio-economical order, they change when the ‘thought style’ of an epoch changes, but it’s not something an individual can deliberately do. Though — individuals can give prompts and incentives that can foster or support changes.

N: Right, maybe we can also bring in the other forms of exhibitions into discussion. You mentioned biannials but then there’s also art fairs that are new places of assembly, also reflective of what’s at the center. Here, again, capital. Some fairs offer interventions, like performances and artist talks, but the principle is not really interpersonal interaction, it is sales and a kind of marker of prestige for the participating artists. So we’ve got social media and art fairs, galleries, biennials and Museums, which are all interfaces through which art can exist. Then, with the policing of public spaces making it harder to create public interventions today, and adding to it highly bureaucratized public funding, it boils down to an uninspiring picture: where influencers, art administrators and sales agents are running the culture. There is a feeling of impoverishment in this 20th century hangover that you also mention in your writing. And I have a feeling that the new ideas keep short circuiting because they are still having to operate within the capitalist system that keeps turning everything into a commodity. In your essay I mentioned earlier you also talk about Margaret Mead and her influence on your thinking. She had decreed the exhibition as a poor ritual already back when. Observing the emerging new formats of art making, i.e immersive exhibition etc, what is the relationship in your view between ritual, entertainment and further commodification of that kind of art format, so experience economy?

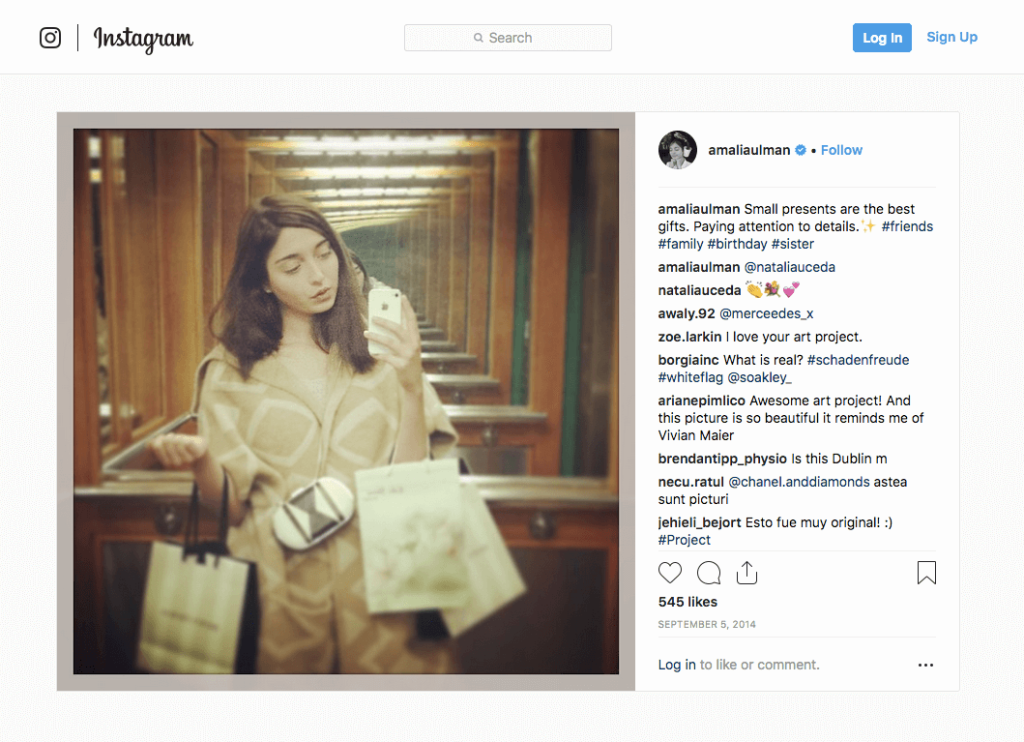

DvH: I think we have to understand that we are in a major moment of transition. Whatever was called “the artworld” in the 20th century, was a very small game, with very few players, and a small number of visitors. The playing field was basically Paris and New York, a few galleries, a few artists, and they were mostly male and white. The discourse was extremely hierarchical and also segregated. And this is also what I meant earlier by saying that art history can be considered a form of esoteric knowledge today. Museums, art institutions and galleries were also incredibly hierarchal, people who produce art moved up levels and at the top was something like MoMA or Guggenheim, and access was controlled by gatekeepers: curators, critics, gallerists etc. It was a hierarchical but also a relatively stable system. This has changed tremendously, and of course digitalization and social media play a huge role in this process. Today anyone can have access to the public, unlike previously, when an artist used to be in a privileged position through exhibiting in a gallery or a museum: a youtube clip can generate more viewers per hour then there’s visitors to a Gerhard Richter show. Today, the term curator is so widely used that it has lost some of its precision. In the presence of digital and social media, we all curate, if you like: Instagram pages, pictures, etc. Material values have shifted to immaterial values, like experiences. And the emergence of experience economy, including immersive exhibitions, is part of that attempt to shift the ritual, as it has always changed in accordance with the major changes within society. I don’t believe the experiential dimension of art is intrinsically defined as positive or negative. I am more interested in how these experiences are made, and why. And my question is: how do we actively want to shape this process, instead of leaving it to corporations that curate, let’s say, immersive van-Gogh spectacles.

AK: I was more thinking of the question of the outcome, because in the end it feels like, after being so bureaucratized and professionalized, even when we change the players, it all folds back into itself all over again. For example, practices like relational aesthetics since their inceptions have also been reabsorbed into that same system of production they seemed to initially want to counter. It’s not a painting, it’s not a urinal, it’s now a video. Today it’s an experience…

DvH: I think your intuition and critique is right, and perhaps that’s why I am placing the emphasis on the format. If the format stays what it is, it’s very hard to implement change. If you walk into a white cube — you are looking for a meaningful object. And if there is only a fire extinguisher there, you’re ready to believe that this is the art object. By now we are conditioned that as soon as we enter this format that we should react and construct what we believe is meaningful. So for things to change it would take a radically different format. But these existing formats are very strong, they are very powerful, because as I said earlier — they are not something that can be just modified on a whim. We spoke about this in reference to the last Venice Biennial, which was an amazing, incredibly well-researched exhibition, featuring many, mostly female artists exploring both historical and contemporary modalities of connectivity and holistic thinking. But the underlying format of the exhibition was still based on the autonomy of the artwork, and then multiple autonomous artworks gathered in one space. So the question for me is — should we, or can we even apply this new mindset of connectivity to the format itself?

AK: I wonder if the replication of previous formats, just with new tools, instead of their reinvention, is connected to what you call invisibility, or unacknowledged quality of rituals today. Not only as related to exhibitions but other: political rituals, social. Next to this invisibility is the trend — in contemporary theory and art — to talk about “re-enchantment of modernity”, presumably as a counter to overdevelopment and alienation. So there’s not exactly a desire for “return”, but a desire to reinvent spirituality and interconnectedness. There is a tension, however, between thinking about exhibition as a ritual vs. the more mainstream societal refusal of acknowledging its rituals, all the while needing rituals as grounding protocols. You have pointed out that familiarity and processes of rituals can be a form of having a “home”. How does this feeling of home, or can it, translate into an exhibition format?

DvH: I think if we take museums as places embodying the values of western modernity, then there is a question of what kind of experience they produce. And I would say it is one of home-lessness. The white cube is a place of homelessness. Hegel can be considered the father of the museum because, as Didier Maleuvre points out in his marvelous book on museums, he made sense of this uprootedness, which for him was an achievement. Because it stands for an individual who has overcome the need for roots and for primordial connections; an individual who achieves a reflected and no longer natural relation to their surroundings. But, as we today find ourselves at the endpoint of this historical process, we look at it differently. As Bruno Latour had said more recently, we have to redefine our notion of home, or ‘soil’ in a progressive way and not leave it to reactionary thinking. I don’t think you can translate these thoughts directly into an exhibition ritual. But they can play in your head as you conceive it. After all, to curate an exhibition is to work on connections: between visitors and artworks, between artworks and the space.

AK: Right, and I guess I was thinking what would it mean for a Museum to acknowledge itself as a place of ritual? How would it shift its form and function…

DvH: I think for a museum to acknowledge the ritualistic power of the format would mean to take it into account and work with that on a more fundamental level than it is currently happening.

AK:With that emerges a heightened sense of responsibility, which brings me to Latour’s quote in your essay: “The task of this new age is not one of critique, but of composition, not of emancipation, but of care.” This seems to presume the process of emancipation as complete, and when put in opposition to each other by such statements, care as not requiring a critical perspective. But in a way how can we know what requires our care if there is no critical framework? How do you think these two things like care and criticism can be part of a new kind of institution without giving up one or the other?

DvH: I think I brought in this quote by Latour when talking about the ontological aspect of art in modernity, which, being based on the idea of autonomy, is one of separation. In the early days of public museums, there were these caricatures of peasants who would come from the countryside to visit the Louvre for the first time, see a painting of a Madonna, and what did they do? They knelt down and prayed. They didn’t understand the shift in mindset: you’re no longer supposed to pray to Madonna, but to critically assess Fra Angelico (as an example). But the act of judgment presupposes a form of distance, of separation. You don’t judge something you believe in. Just as the Madonna painting underwent an act of separation from its original context (of e.g. the altar in a church) to the museum, the modern way of relating to art presupposes some form of critical distance as well. This modality of critique has been a fundamental driving force of western modernity. And it has achieved a lot, without doubt. But what historically has been an achievement might no longer be sufficient to solve the problems we are facing today. From today’s perspective, where the social, ecological, economic, and psychological consequences of this attitude of separation press irrefutably into consciousness, where society as a well as people are sickened by their inability to envision wholeness, we start to become aware of the limitations of a culture that has an incredibly advanced culture of critique but no longer knows any form, practice, or ritual for wholeness.

AK: And as part of achieving that, in your writing you suggest that a new artspace would need to be interdisciplinary, and that means without specialized departments but more of a kind of consortium of activity. Interdisciplinarity is something that many institutions have already begun to consider. However, it remains a tangential engagement, and the majority of educational and cultural institutions are very fearful of the disciplinarian drift, and specialization is structurally rewarded. To really embrace speaking across disciplines we all would have to be prepared to be a little uncomfortable in this scenario, and a little humble, and out of depth. But in my experience, efforts to do this, to be this messenger between systems and disciplines, remain to be fool’s errand because they are systematically blocked — through curriculums, funding, hiring processes and programming choices. As a result, if one does work across fields, it can act as an invisibility cloak because one is simply perceived as inexpert. So how do we arrive at interdisciplinarity from this juncture and leave behind the rigidity of the current system?

DvH: The model of specialization has initially, and over a long period of time, achieved great wealth and welfare effects. However, these effects become progressively smaller, moreover, they have produced consequential damages, be they of an ecological or of psycho-social nature. And these welfare damages have to be included today, which can only be addressed with difficulty by the current culture of specialization.

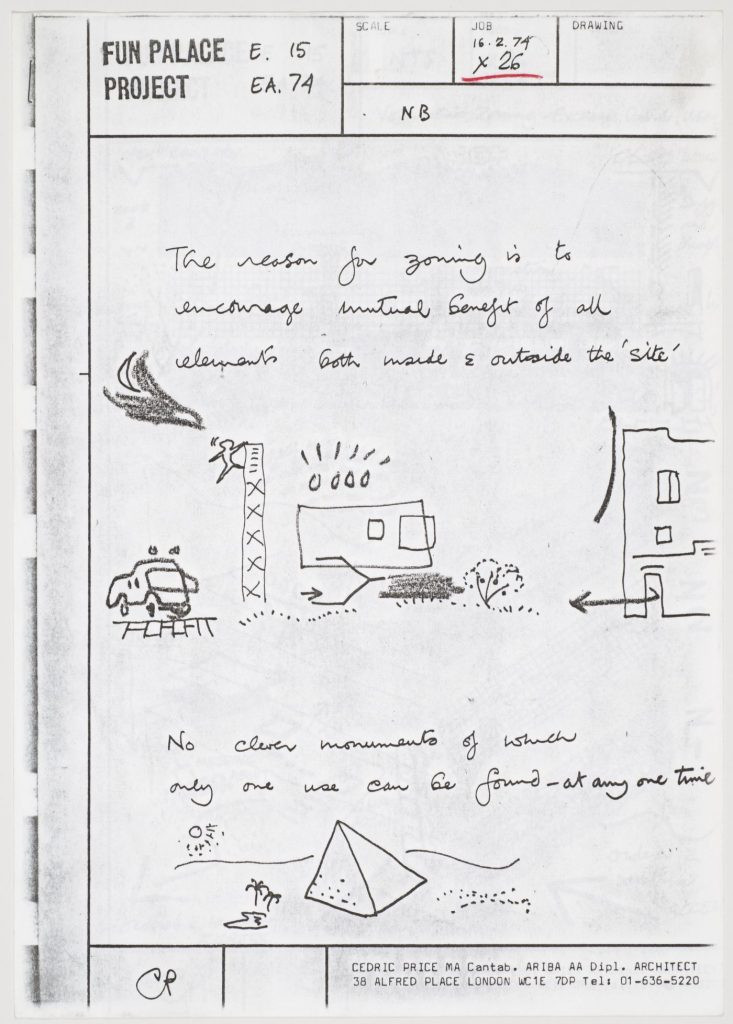

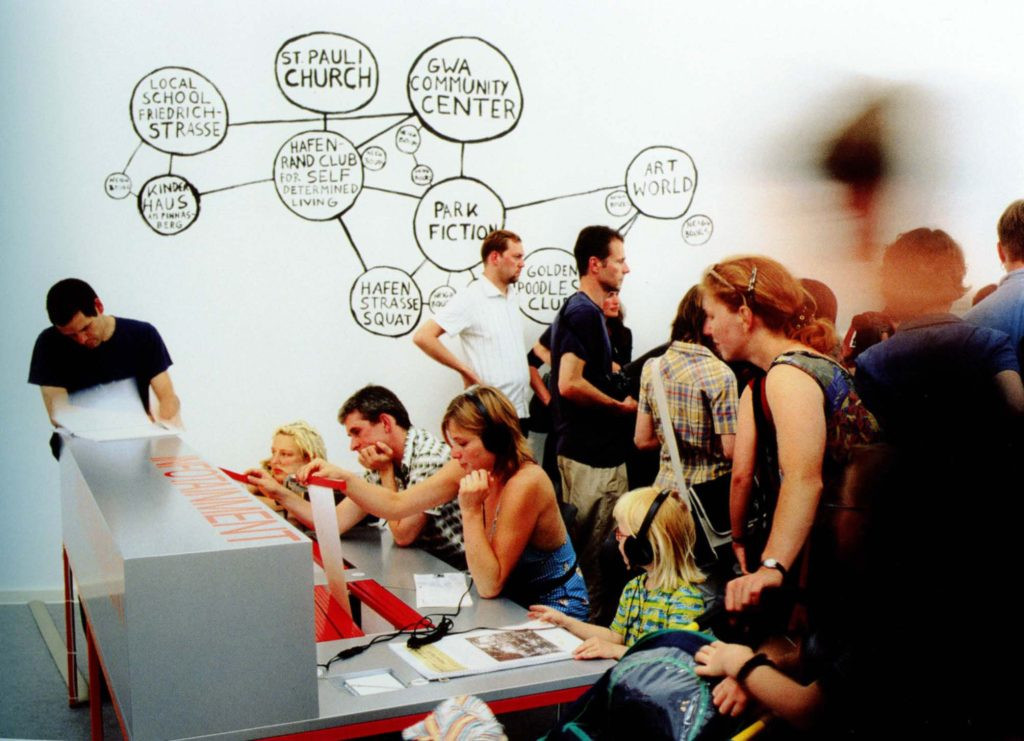

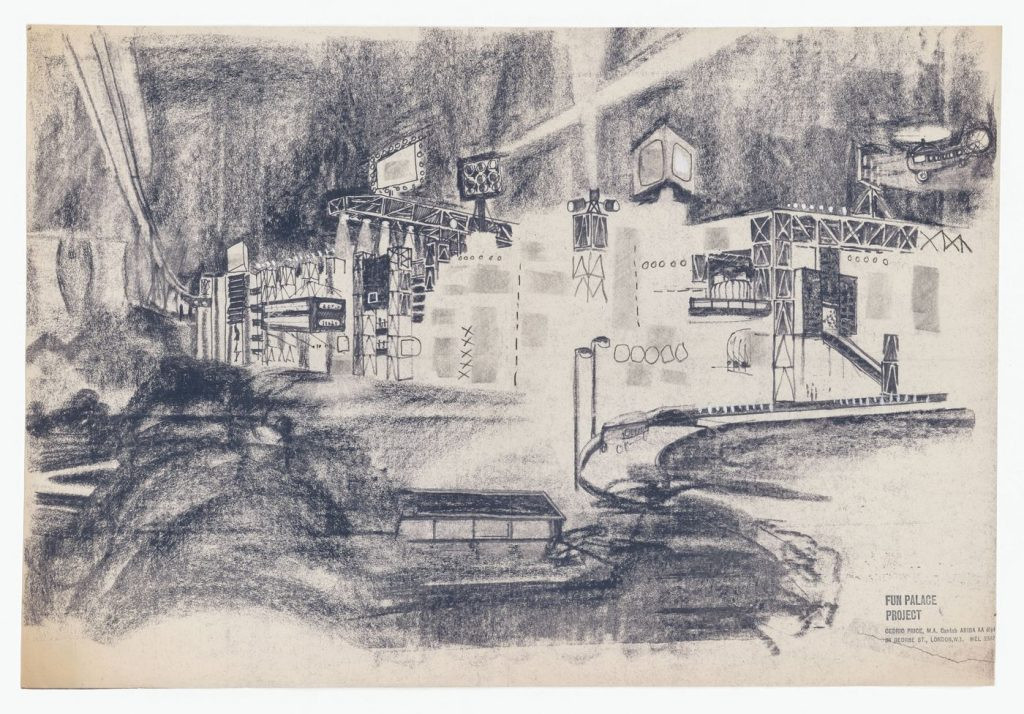

So while I would struggle to answer the question of how to get there on such a broad level, it would be interesting to look into the history of institutions as food for thought. For example, the “Fun Palace”: a very experimental and never realized, nevertheless very influential, idea from the 1960s —of a new kind of institution, conceived by architect Cedric Price and theater director John Littlewood.

The Fun Palace radically re-defined the idea of what an institution could be: rather than a container in which pre-determined things happen, it was conceived as a temporary, unstable structure that could respond to ever-changing ways of using it by changing its form. It was radically post-disciplinary, if you like, in the sense that it didn’t even think any more in terms of disciplines. Stages and exhibition spaces, cinemas and open meeting rooms, workshops, a library and even a circus tent were envisioned. Not everything about this project was convincing. The focus was so strongly on breaking down rigid rules and hierarchies, but it was not quite clear what was actually supposed to take their place. Also, the ‘vertical’ dimension of excellence or ‘specialist’ did not exist at all. So it was equally unclear what the place or the role of ‘art’ would have been in a place such as this. But as a vision, it still remains very inspiring.

The Centre Pompidou in Paris, opened in 1977, was built taking the Fun Palace as an explicit reference. But in the end, the reference is more external, concerns more the appearance, whereas inside it remains a relatively traditional space. It is interdisciplinary, yes: there is a theater, a museum, and cinema. But it’s also very conventional, because each of these artforms have their own department and floor, their own production teams, their own budgets. So they might all be housed in one building but they are not connected.

So how do you really connect these disciplines? Yes, here things immediately become very complicated because of expertise in one field and not in the other, and technical skills etc. Yet it’s not impossible. I think it’s just a question of time and training and inventing. Ten years ago at Goldsmith, a student I met for a studio visit, who was interested in bringing together dance and photography could not find anyone to speak about dance next to the photographs that they took. And this was despite Goldsmiths' vast research resources and rich history of analysis of visual culture. Since then the situation has slowly changed. Most art schools today are still not Bauhaus or Black Mountain.

AK:Thinking about visionary institutions, I was also remembering Dispossessed by Ursula K Le Guin and the idea that on the speculative anarchic planet Anares, wherever you went, you would always have a place to sleep, eat, you’d have work projects to sign up for, or a place for public engagement. There is a description of a regional gathering space in the book, let’s say it would be one or several per kietz, if we take Berlin, that would be free to use, one would just have to just book them. The imaginary Anares does have a much smaller population. Not to say it’s an impossible idea for that reason on planet Earth. Most galleries, museums, residencies, in my experience, remain deeply insular, and these traditional institutions still exude an air of superiority, where whatever is“public or peripheral is perceived as necessarily “bad”: bad taste, bad quality, or is under-considered; and conversely what is institutional — is necessarily better because it is made by experts. This is, of course, not supported by evidence. There’s plenty of underwhelming exhibitions and programming out there all the time, and even purportedly interdisciplinary new institutions can be ill-conceived, like The Shed ended up being in New York, and Humboldt Forum is in Berlin. So how do you think experts and the public could come together within a new format?

DvH: One of the things the anthropologist Maragret Mead observes in her critical perspective on the modern notion of art, is that it made the artist into an exceptional figure that has some kind of privileged connection to creativity that the rest of us presumably does not have. This is how museums are built: the general public is invited to observe the exceptional genius. And that, I believe, is one reason why my students don’t want to go to museums any longer, or see them as slightly dated: because this kind of thinking does not reflect their reality. For the better or worse, creativity is part of many people’s daily life. And I don’t mean that I think everyone should be creative, and needs to be that all the time, but we are living in what Andreas Reckwitz calls the ‘creativity paradigm’.

Creativity has shifted, from the margins of its previously exceptional status, to being, more and more, a cultural, social and economic pillar of society. That does not mean that we’re all artists, in the sense that Joseph Beuys had envisioned it. But it might mean that the difference between those who are artists and creative, and those who are not, today is, at least in historical comparison, more a matter of degree than of category. And that’s why I found Margaret Mead’s perspective very interesting, because she says: that’s how it functions in traditional rituals, an artist is someone who can do something, in a more specialized way than others—for example someone who is very skilled in a certain craft—but it’s a craft that in principle is available to everyone. And this, I think, reflects more accurately where we are headed. We are already all image producers with our phones, which is a radically different position than what it was a century ago. What remains is to radically reassess the notion of passivity and activity of participants within the institutions. In small steps this is already happening: it is not a coincidence that workshops have become so popular as a format within museums and cultural institutions. It’s a format that is very fluid, and offers a range of options for passive or active participation. It may be that it has potential that we are only starting to understand!