“White Clouds Drifted High, their Shadows Gliding over Clover”

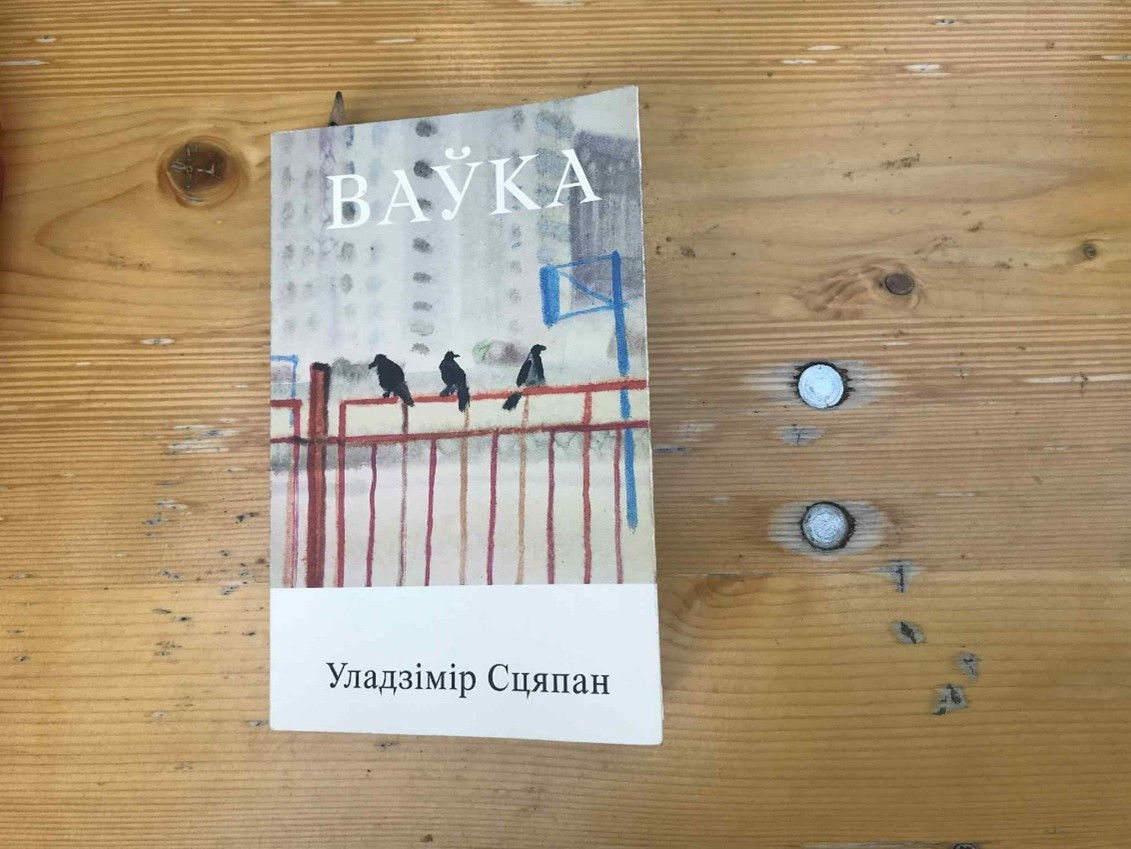

Olga Bubich reflects on the way Uladzimir Sciapan talks with the dead in his new book Wauka published with Mianie Niama independent Belarusian publishing house in exile.

Explaining foreigners why Belarus is not Russia and how come the Russian language is not the same as Belarusian does feel like a job it itself, invariably risking turning any innocent “where are you from?” small talk into a geopolitical lecture. And — trust me — not every white, middle-class male interlocutor, often lacking even a basic understanding of history of any state beyond the EU’s borders, is humble or well-mannered enough to admit it. But an even harder task is to enlighten foreign interlocutors about my homeland’s religious dimension.

Back in my university days, it was Iryna Burdzjaleva, Belarusian Literature Professor, who gave the enigma of our belief system its most accurate framing, defining Belarus as the most Christian of all the pagan states, and the most pagan of all Christian. Try to ground it in a conversation with a foreigner — a Dutch protestant or a fan of the newly proclaimed first millenia saint, for instance. “Some people need the cemetery, others don’t. But who is the pagan here?” wondered an atheist EU-born friend of mine in a sincere attempt to grasp the Belarusian soul mystery.

Well, how can one rationally explain it that in Belarus the border between the worlds of the living and the dead is so thin, that those who find themselves on the other (either?) side are able to regularly cross it — showing care and love, or warning against a possible danger. In doing this, we, cursed holders of the blue passport with a Soviet coat-of-arms on its cover, finally need no visas, embassies, or a documented purpose of the visit.

And if I were to imagine a universal image to describe how this trespassing occurs and which actual figure facilitates it, I’d name Uladzimir Sciapan — the Charon of Belarusian contemporary literature, whose collection of short (and very short) stories has recently been published by Mianie Niama independent publishing house, since 2021 in exile in Poland.

Wauka miniatures are meant to be read after eight, preferably with no distractions — including people — around. They are to be immersed in those timeless intraseasonal hours that in the early 20th century the Russian anti-Bloshevik writer Ivan Bunin defined as requiring a word of their own, “sumernichat”. To witness the day transitioning into night without turning the lights on — a perfect setting for the acquaintance with Sciapan’s host of ghosts. However, if instead of a poorly-lit kitchen or a village cemetery bench, you happen to be squeezed — an open book in one hand and a subway handrail in the other — into the collective body of metropolis commuters on their regular way home from a regular weekday at the office, no need to worry. Keep on reading, Charon would find you anyway. Just stay alert to get off at the right station.

Almost any character from Sciapan’s forty-eight stories can vividly illustrate what Belarusians’ unique perception of the world of the dead is. The reasons for this are two: his narrators have either been in contact with Charon after losing their close ones, or they themselves are the upper world’s dwellers. The ghosts of former school friends — suicided, murdered in a street fight, or lost in a battle with cancer, — deceased grandparents, silent neighbors, sick cats, and even crows are going to be there to talk. Just keep on reading. Be there to listen, despite your own memories soon overflooding the voices of the book heroes.

“We walked the field path: Granny Natallya, the red cow Zorka, and a boy who would soon be a first-grader. White clouds drifted above, their shadows gliding over the clover. I held the rope that bound me to the cow, to Granny, to the road, and to that wide, cloud-bright sky. When the rope breaks, I will no longer be there anymore, ” writes Sciapan in one of his miniatures, and you automatically reach out for your own invisible umbilical cord. Are you still a part of your own living chain? Are you still there yourself?

When I mention Sciapan’s ability to change the space around you — once you are down the Wauka’s hole — it’s not my writer’s exaggeration or a cheap way to attract your attention: his existential interiors are indeed full of temperature- and touch-based metaphors, which, travelling in a paraphrased version from story to story, start producing almost a tangible, physical, skin-sensed impact on the reader. And the central role here is played by the kitchen — almost the only place where, both back in the Soviet times and in today’s Belarus — people could feel safe and free to express themselves and be critical of the system they were forced to be a part of.

However, the kitchens where the dead and the living get together in Wauka differ from those of everydayness. The past seems to be densely present in those empty cold rooms to a larger extent than their present: it is more the unspoken that dominates the setting, as well as silence, a mere sensation of someone or something important — lost, found and then lost again, — or spontaneous small gestures that reveal hidden genuine intentions. Like a woman from Wallpaper miniature who, on hearing about the death of her former lover, suddenly stands up and goes to the hall to vigorously tear off the wallpaper, starting off the repair works postponed for long.

Does the encounter with death make us inventory our lives? Is it capable not only of taking away but also of repairing, of starting something anew?

Every spring, on the ninth day after Easter, Belarusian cemeteries, or mohilki, as we call them in our language, would get busy with the living returning to their dear dead: cleaning and refurbishing their last place of rest, sharing bright memories and latest news. Accepting the universality of the imminent destination. Following an ancient pagan tradition, merged with the Orthodox norms — in Belarus much looser than in the neighboring Russia — the day of remembrance is an integral part of our people’s calendar. Radunitsa, also a public holiday, stood for a moment of union, a reason to get together… and rejoice. The very word the name of this day came from means radasts — joy.

In his book with the self-explanatory title Being with the Dead Swedish philosopher Hans Ruin suggests, when taking about our relations with the deceased, to replace the word responsibility with responsiveness, arguing that the former assumes rather a moral and legal context, while “in the domain of being with the dead there is no certainty or definite rules”. There isn’t, indeed. We would never really know what the dead want from us, or fully embrace what we owe to them, but being with the dead in a way our culture naturally invites us to do is a way of accepting the existence of something we still share with them — beyond what one is able to perceive with senses, intuitively feel, or rationally understand.

In this light, the collection of Uladzimir Sciapan’s short stories appears to be more than literature dedicated to the living, the dead, and the disappeared in the terra incognita of Belarusian forests in the 1930s or Belarusian prisons in the 2020s — in the geographical center of Europe. It’s a glimpse at what life is for us. After all, the book’s own untranslatable title already hints at this conclusion. Because wauka — a little wound one is either already treating or has given hope to cure and thus embraces it as it is — might also be about what one feels when losing a grandparent, a spouse, a former friend, a silent neighbor, or an old cat. Because the emptiness every time someone is gone would never be filled or fully healed and to embrace it is the only thing one can do. Dedicating them your memories, writing them your stories, bringing them food on the ninth day after Easter — making sure that the rope is still there to bound you. That it hurts a bit less. Because the way we treat our dead speaks much more about us, our morals and society, than about the dead. And this is what we believe in in a place where I was born.

Berlin,

2025