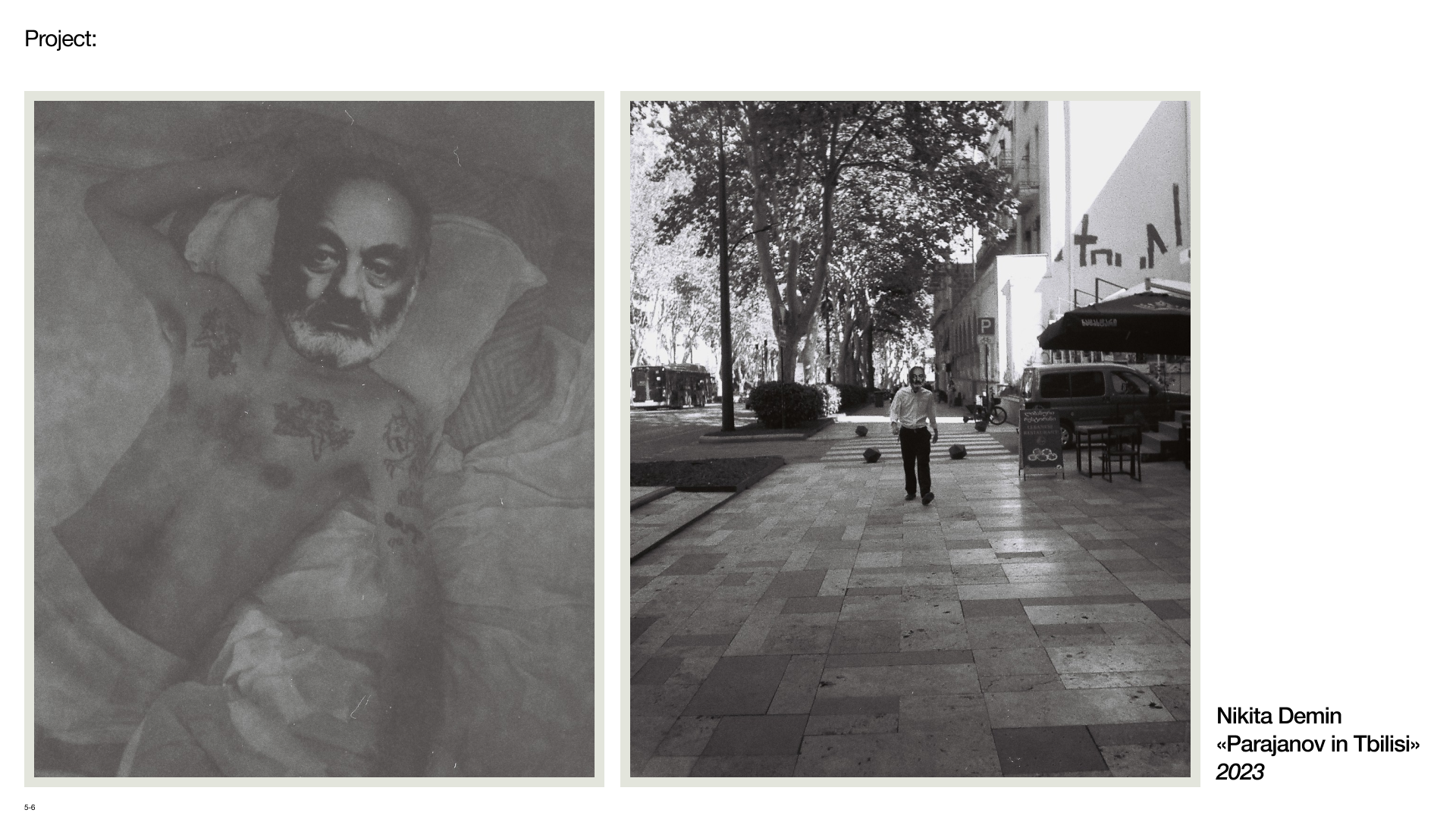

Reenactment «Parajanov in Tbilisi» (ENG/RU)

48 years ago, on April 25, 1974, together with seven other defendants, Sergei Parajanov was sentenced in a closed court session by the Military Tribunal of the GSSR Interior Ministry troops to 5 years for “sodomy”.

This round date is so fiercely sharpened in my mind because of the contemporary context of the post-Soviet world: where one is still proud of the victories, flights, “successes” of the past, going into the future carrying strife and the eternal war of all against all, the battle of the weak for a place among the strong, Thatcherism and neoliberal values. “We’re not homophobic, transphobic, racist, but…”. But, in fact, no one who displays and carries any otherness — there is no place without a fence, past a convenient museum or controlled institution where it will be something like “degenerate art” with which to frighten the common man.

It“s an endless affect, a hypocritical democracy, we constantly hear about how new rights are being taken away everywhere: today you can”t love, tomorrow you can“t walk. But you can: sit not to stand in a forbidden position, and also not to be gay, lesbian, bi, etc. You can”t change your sex, gender, appearance, have views, have yourself.

In his most famous work “One Day This Child” (1990), American outsider artist David Wojnarowicz vividly expressed the situation that happened to Parajanov in Tbilisi half a century ago, expressed the status quo of today:

"…One day politicians will pass a law against this child. One day, families will start telling untruths to children, and children will pass these lies to their families from generation to generation to make the child’s life unbearable. One day the child will feel all this around him and will want to kill himself or put himself in danger in the hope that he will be killed, or shut up forever and become invisible…"

And further:

"…The child will have his constitutional right to privacy taken away. He will be prescribed drugs, electroshock, reparative therapy in laboratories under the supervision of psychologists and scientists. His home, civil rights, job, and all possible freedom will be taken away. All of this will happen a year or two after he first wants to press his naked body against another guy’s body."

One day last spring, when I was in Tbilisi for the first time, I rather unintentionally came across Olivia Lang’s book The Lonely City.

I was sitting in the middle of a foreign space, at yet another sleepover, reading the chapter on Wojnarowicz. It talks about a series of works from '78-79 called “Arthur Rimbaud in New York.” Wojnarowicz saw in Rimbaud his reflection, an imprint of injustice. Not only that, but he like Rimbaud died at the age of 37.

Now I am 22, this text, like my unborn relative, ten years older, resonates in me, ossifies. I constantly feel like a child who has grown very abruptly, a child who has had another channel of air cut off, another cell painted over for going forward, going backward: there are fewer and fewer cells. Time is running faster, cells are shrinking,

I am growing upwards and space is shrinking.

At the same time, in the spring of 2022, I watched, listened and read a lot about Sergei Parajanov. An artist who is proud of in Transcaucasia. An artist whose works one wants to look at and admire. Many people consider him their treasure. But almost everyone who knows that Parajanov was gay either doesn’t believe it or scoffs at it. And I found this series of — coincidences that we are forever looking for, finding, believing — all three artists were gay and all of them experienced institutional/societal persecution for their sexuality interesting.

How many other French people spat when they found out a great poet was a butch? How many Americans have done so? In 2023, I saw Parajanov being laughed at. Why do we turn our backs on this truth, close ourselves off with convenient museum displays of the author and cover up the huge birthmark of his personality?

They were superfluous. It’s time to recognize that even now they are “different” and “superfluous.” And it seems to me that the prolongation of this performance — a portrait in the midst of a city where the author is definitely no longer there, no longer with his feet on the pavement — is an excellent occasion to remember hypocrisy, silence and the status quo, which will hardly change even when I, too — still a young man, it seems — will pass away.

I find this triumvirate very integral and appropriate: poet, director, artist. Each in their own way an outsider, deliberately going off the edge of the visible realm — garish, awkward, unprofessional, whatever. Constantly interacting with art — I do so while being conscious of my ineptitude, even loving it.

Silence is death. I think we need to learn not to be silent and to speak, no, even shout about things that are disturbing.

This is a project I“m publishing today, taking a long time to decide to do so because I probably don”t have much of a voice for the people I“m talking about. I don”t have an active gay experience, I“m not in a relationship with a man*, and I don”t define myself as gay or interested in men*. But I don“t think I can define my sexuality in any clear way, and it”s fortunate, in today’s world, to have left a country where such a thing is a criminal offense — a privilege I intend and am even happy to take advantage of.

2023, Tbilisi, Georgia.

Russian Bellow

48 лет назад, 25 апреля 1974 года вместе с семью другими обвиняемыми Сергей Параджанов был осуждён на закрытом судебном заседании Военным трибуналом войск МВД ГССР на 5 лет за «мужеложство».

Эта дата так ожесточенно заостряется в моем сознании

Но, на самом деле, никому из тех кто отображает и несет в себе любую инаковость — нет места без ограждения, мимо удобного музея или контролируемой институции, где это будет что-то вроде «дегенеративного искусства» которым будут пугать обывателя.

Это бесконечный аффект, лицемерная демократия, где мы постоянно слышим о том как забирают все новые права повсеместно: сегодня нельзя любить, завтра нельзя ходить. Зато можно: сидеть чтобы не стоять в запрещенной позе, а еще не быть геем, лесби, би, etc. Нельзя менять свой пол, гендер, внешность, иметь взгляды, иметь себя.

В своей самой известной работе «Однажды этот ребенок» (1990) американский художник-аутсайдер Дэвид Войнарович ярко выразил ситуацию которая произошла с Параджановым в Тбилиси полвека назад, выразил статус-кво сегодняшнего дня:

«…Однажды политики примут закон против этого ребенка. Однажды в семьях детям начнут рассказывать неправду, и дети будут передавать эту ложь своим семьям из поколения в поколение, чтобы сделать жизнь ребенка невыносимой. Однажды ребенок почувствует все это вокруг себя и захочет убить себя или подвергнуть себя опасности в надежде, что его убьют, или замолчать навсегда и стать невидимым…»

И далее:

«…У ребенка отнимут конституционное право на частную жизнь. Ему пропишут препараты, электрошок, репаративную терапию в лабораториях под присмотром психологов и научных работников. У него отберут дом, гражданские права, работу и всю возможную свободу. Все это произойдет через год или два после того, как он впервые захочет прижаться голым телом к телу другого парня.»

Весной прошлого года, когда я впервые оказался в Тбилиси, мне довольно не случайно попалась в руки книга Оливии Лэнг «Одинокий город». Я сидел посреди чужого пространства, на очередной ночлежке и читал главу о Войнаровиче. Там рассказывается о серии работ 78-79 годов под названием «Артюр Рембо в

Мало того, он подобно Рембо погиб в 37 лет.

Сейчас мне 22, этот текст, как мой нерожденный родственник, на десять лет старше, отзывается во мне, осиняет. Я постоянно чувствую себя ребенком, который очень резко вырос, ребенком которому перекрыли еще один канал воздуха, закрасили еще одну клетку для хода вперед, хода назад: клеток все меньше. Время бежит быстрее, клетки уменьшаются, я расту вверх, а пространство — сужается.

Тогда же, весной 2022, я много смотрел, слушал и читал о Сергее Параджанове. Художник которым гордятся в Закавказье. На работы которого хочется смотреть, засматриваться. Многие считают его своим достоянием. Но едва ли не каждый кто знает о том — что Параджанов был геем, или не верит в это, или насмехается над этим. И мне показалась занятной эта череда — совпадений, которые мы вечно ищем, находим, которым верим — все три художника были геями и все они испытывали институциональные/общественные гонения за свою сексуальность.

Сколько еще французов плевалось, когда узнавало что великий поэт мужеложец? Сколько американцев делали так?

В 2023 я видел как смеются над Параджановым. Почему мы отворачиваемся от этой правды, закрываемся удобными экспозициями автора в музее и закрываем огромное родимое пятно его личности?

Они были лишними. Пора признать что и сейчас они «другие»

и «лишние». И мне кажется, что продление этого перформанса — портрета среди города, в котором автора уже точно нет, нет ногами на асфальте — отличный повод вспомнить о лицемерии, молчании и статусе-кво , которые едва-ли изменятся даже тогда, когда и я — вроде бы еще молодой человек — уйду из жизни.

Мне кажется очень цельным и уместным этот триумвират: поэт, режиссер, художник. Каждый по своему аутсайдер, сознательно уходящих за край видимой области — аляповатые, неловкие, непрофесиональные, как угодно. Постоянно взаимодействуя с артом — я делаю это, сознавая свое неумение, даже любя его.

Молчание — смерть. Думаю, нам нужно учиться не молчатьи говорить, нет, даже кричать о тех вещах, которые тревожат.

Этот проект я публикую сегодня, долго решаясь на него, потому как наверное не очень имею право на голос за тех, о ком говорю. У меня нет активного гей-опыта, я не состою в отношениях с мужчиной* и не определяю себя как гей или человек которому интересны мужчины*. Но я не думаю, что могу определить свою сексуальность как-то четко, и это, к счастью, в современном мире, уехав из страны где подобное — уголовное преступление — привилегия, которой я намерен и даже рад воспользоваться.

2023, Тбилиси, Грузия

Support Charity Info:

Tbilisi Pride

NPO/LGBTKIA+

Tbilisi Pride is a relentless LGBTQ+ movement that believes in the idea of equality. It fights tirelessly and consistently against homophobia and transphobia, constantly striving to create safe and inclusive spaces and to self-develop.

The mission of Tbilisi Pride is to create an equal and free environment for LGBTQ+ people. This is achieved by putting community challenges on the political agenda, empowering the community and changing public opinion.

To accomplish its mission and goals, Tbilisi Pride primarily employs a visibility policy as its main tool.