Ruslan Nasir AW2022 'My Old Man'

Ruslan Nasir's approach is an interdisciplinary one: fashion for him exists in close connection with other artistic practices, such as literature and music. Nasir’s longtime dream was a fashion review written by his close friend Misha Zakharov, a Russian-born film critic, writer and translator of Korean heritage. In the first chapter of his debut book, which was due to be out in the spring of 2022 via No Kidding Press, Misha talks about how his father abandoned their family and returned to Korea. Due to the economic collapse caused by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the publication of the book has been postponed indefinitely. Currently Misha is working at the Venice Biennale, but Nasir’s longtime dream nevertheless came true — albeit in the new reality where we all live now.

Прочитать рецензию на русском языке можно здесь.

By Misha Zakharov, June 2022

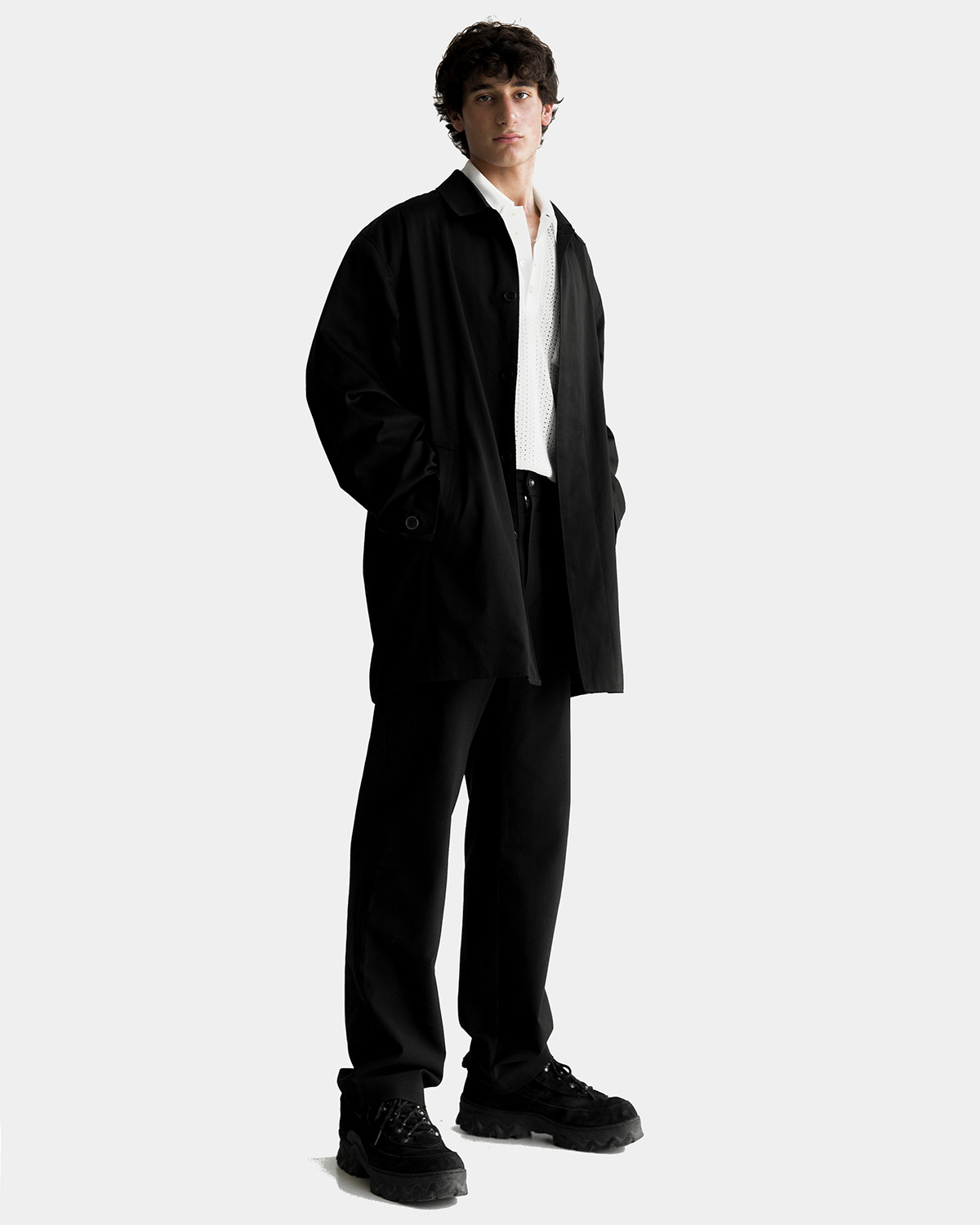

The title of Ruslan Nasir’s graduation project refers to Joni Mitchell’s song My Old Man from the legendary album Blue. The man to whom it is dedicated to sings in the park, walks in the rain and dances in the dark; he is Mitchell’s sunshine in the morning, her fireworks at the end of the day and the warmest chord [she] ever heard. In The Kids Are All Right, a lesbian couple portrayed by Julianne Moore and Annette Bening is surprised, if not shocked, to learn that Mark Ruffalo’s character — the heterosexual biological father of their children — loves the album, too. Indeed, Blue can hardly be called a heterosexual record, and the song My Old Man, although dedicated to a man, treats his image as something impressionistic and ephemeral. Nasir follows the same approach, dressing a multi-ethnic, mixed-age group of men — by turns relaxedly brutal and impregnably fragile — in refined items of varying sizes.

At Ruslan’s request, I try to imagine wearing his clothes, but there’s a problem, because four months ago, after the start of the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Nasir fled Moscow, and so did I, now based between Venice and Tashkent. It is unlikely that the designer will send me the parcel. Besides, he’d never let me try his clothes on before — will he finally keep his promise now, in the face of the end of the world?

In Uzbekistan, as you probably know, homosexuality (or more precisely, sexual relations between men) is criminalized and any manifestations of femininity (whatever that may mean) on the part of men are condemned. In this context, Nasir’s outfits would come very much in handy: low-key, but with a slight touch of gayness, they would sufficiently distinguish me from the crowd without endangering me. The guys in the lookbook, dressed in oversized blouses, shorts and trousers, look as if they have surreptitiously taken their fathers’ clothes and imitate them in front of a mirror. At the same time, they seem to be emphatically out of character: their trousers are shorts-trousers, while their shorts are shorts-skirts; they are wearing blouses, not shirts, while the key tactile trigger associated with the father — his belt — does not support the stomach, but encircles the chest. Deliberately rough textures are combined with natural silk, satin and translucent hand knitting. In this free, flowing monochrome — white, black, gray and brown — I would move through the streets of homophobic Tashkent in the midst of chilla — a 40-day period of windless heat — as if in a protective cloud.

In the visual study that precedes the collection, Nasir mentions Abbas Kiarostami, whose films we watched as part of last year’s retrospective at the Garage Screen Summer Cinema, for which I wrote the texts. At an early stage in his career, Kiarostami worked extensively with the theme of childhood and examined school as a tool for instilling an authoritarian ideology. He stayed in Iran to the very end, but ultimately, like many representatives of the creative intelligentsia, he also had to leave, shooting his last two features in Italy and Japan. Can these films be considered Iranian? And can the collection of a designer from Tatarstan, the principal figures of which are Armenians, Lebanese, Tunisians, Azerbaijanis, Georgians, Turkmens and Afghans, be considered Russian? What determines the nationality of a cultural product? Author’s citizenship? Country of origin? Alma mater where the graduation project is presented?

There’s a sad irony to the fact that Abbas Kiarostami, one of the key inspirations for this project, turned out to be a useless father figure. In June 2022 an open letter from the director and artist Mania Akbari was published, in which she, who played the main role in Kirostami’s film Ten, accused him of artistic plagiarism, as well as psychological and sexual abuse. Her statement was backed up by her daughter Amina Maher, who played the role of her son in the film and came out as a transgender woman in her adult life. Now Kiarostami’s films about plagiarists and impostors such as Close Up have to be reevaluated.

Each piece of clothing in Nasir’s collection is named after a specific male archetype: the brother who lent you his white polo; a lover, whose own clothes, silky and seductive, you can wear on a date with him; a father whose wide trousers you long to sneak from the wardrobe; and, finally, the guide, represented in the form of a coffee colored satin set with a scarf covering the head. Many men of military age who fled Russia, including Nasir and myself, now have to urgently master these roles — the last two in particular. The collection gives you an opportunity to literally try them on for yourself.

While in exile in Uzbekistan, I did what I previously thought of as unthinkable: I wrote to my father in Korea, whom I had not seen for twenty-one years, with a request to acknowledge paternity. My father responded only two months later, writing to my mother that he had undergone cancer surgery and could not get in touch. When I think of Misha, my heart hurts, he wrote, and yet he did not lift a finger to bring me to Korea. What I want to say is, Dear Ruslan, in the absence of fathers (as well as in their helpless presence) and at a time when the world is on the threshold of World War III (or when, as some believe, it has already crossed it), let’s not forget about our responsibility to each other — for this we, as Joni Mitchell put it, don’t need no piece of paper from the city hall.