Learning to Hear Memories that Talk in Whispers

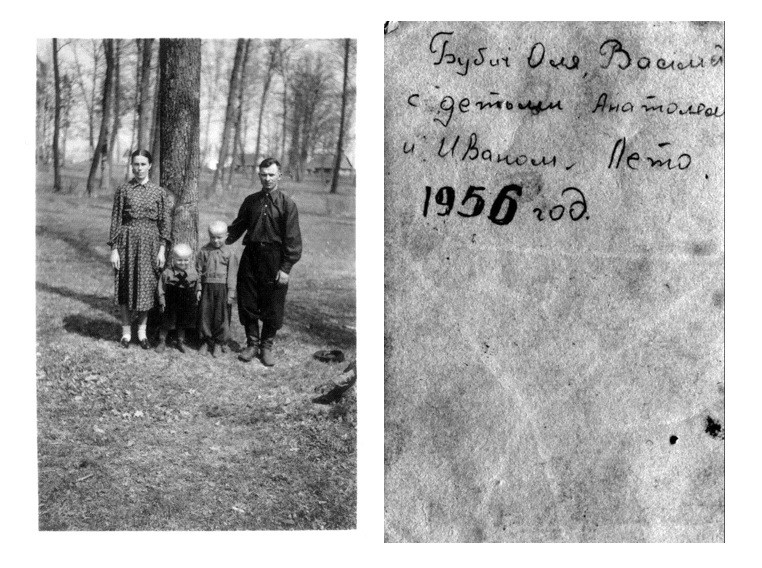

Dedicated to my grandparents:

Olga and Vasily Bubich, Maria and Stanislaw Kozel, Illiya Golikov

When I look at the rare images of my grandparents’, I never see them smiling. Even when photographed in casual situations, they sit or stand calm and composed, as if fully aware of the shooting process' long-lasting importance. With their lips tightly closed and eyes squinted, they seem to be able to exchange glances with today’s adult version of me — facing immigration, switching countries, flats, and jobs, but remaining true to myself and my people. True to the memories I have of those who seldom talked about themselves. Voicing the lessons of their past is my duty.

Born and raised in the rural Belarusian south, Grandmother Olga and Grandfather Vasily were forced into adulthood too soon. Both spent their childhood years working hard for a Bolshevik’s kolkhoz: trembling thin ink lines of Vasily’s autobiography now available in online archives say that he was enrolled into one… at the age of 5. Olga was not encouraged into schooling, either — just like her future husband, she dedicated her entire life to hard manual labor kolkhoz asked for. When the war broke up, putting her life at risk, she helped partisans stationed in the forest nearby bringing them food and supplies. And it was there, by the way, where she would get to know my Grandad. In peace decades, however, she seemed not to show interest in books or traveling, either, although both Vasily and she did all they could to ensure their kids education. Two out of four made it to academia. “No time for this,” she would cut short when asked her about her own studies, at dawn leaving to milk the cow with her firm steps echoed by the loud rhythm of an empty tin bucket. I wonder whether she really had a choice — in the end, it was farmers and workers that the Soviet empire needed, not intellectuals.

The silent closure of the war generation is explicable — finding vocabulary to describe what the Belarusians went through in WWII is not easy. “During his service in the detachment, demonstrated composure and stamina, in battle — disciplined and brave. Morally stable,” I read about Grandad Vasily in a partisan personnel record sheet, one of the few surviving documents that date back to the 1940s. How can I get to know what is written between these lines — keeping in mind that this “composed” referee was only 19 years old? However, despite young age, he went to the frontline that was literally around the corner — during WWII the entire territory of Belarus was a battlefield. In July 1943 Vasily joined a partisan brigade to protect the civilian population on the occupied territories, two months after his native village Bolshie Gorodyatichi, Luban district, was almost fully destroyed by the Nazi. Personal recounts of Vasily’s elder co-partisan about this tragedy (cited as Zheltov M.A.) can also be found online.

1 — 12 March, 1943

“During this time, the brigade had two clashes with the punishers, about 100 Nazis were killed. Our losses are minimal — just a few wounded. The Germans set fire to all the nearest villages — Bolshie and Malye Gorodyatichi, the 5th Brigade, Kuzmichi and others. Civilians were herded into a barn or a house, the door and windows tightly boarded up and set on fire… After the bloody massacre, we are terrified to approach the place. The corpses are decomposing, and there is no one to bury them. The history of humankind has never faced such savagery… Villagers warned by partisans manage to flee into the forests and swamps. From airplanes the Germans keep on bombing the settlements they failed to burn down.”

Today I know nothing of my Grandad’s family that used to live in Bolshie Gorodyatichi. Did the partisans manage to timely warn them about the Nazi’s planned attack or were they caught off guard? Did the 19-years-old Vasily return to the site of the massacre? What did he find there? What did he keep silent about? But what is known for sure — this brutal execution was one of the many…

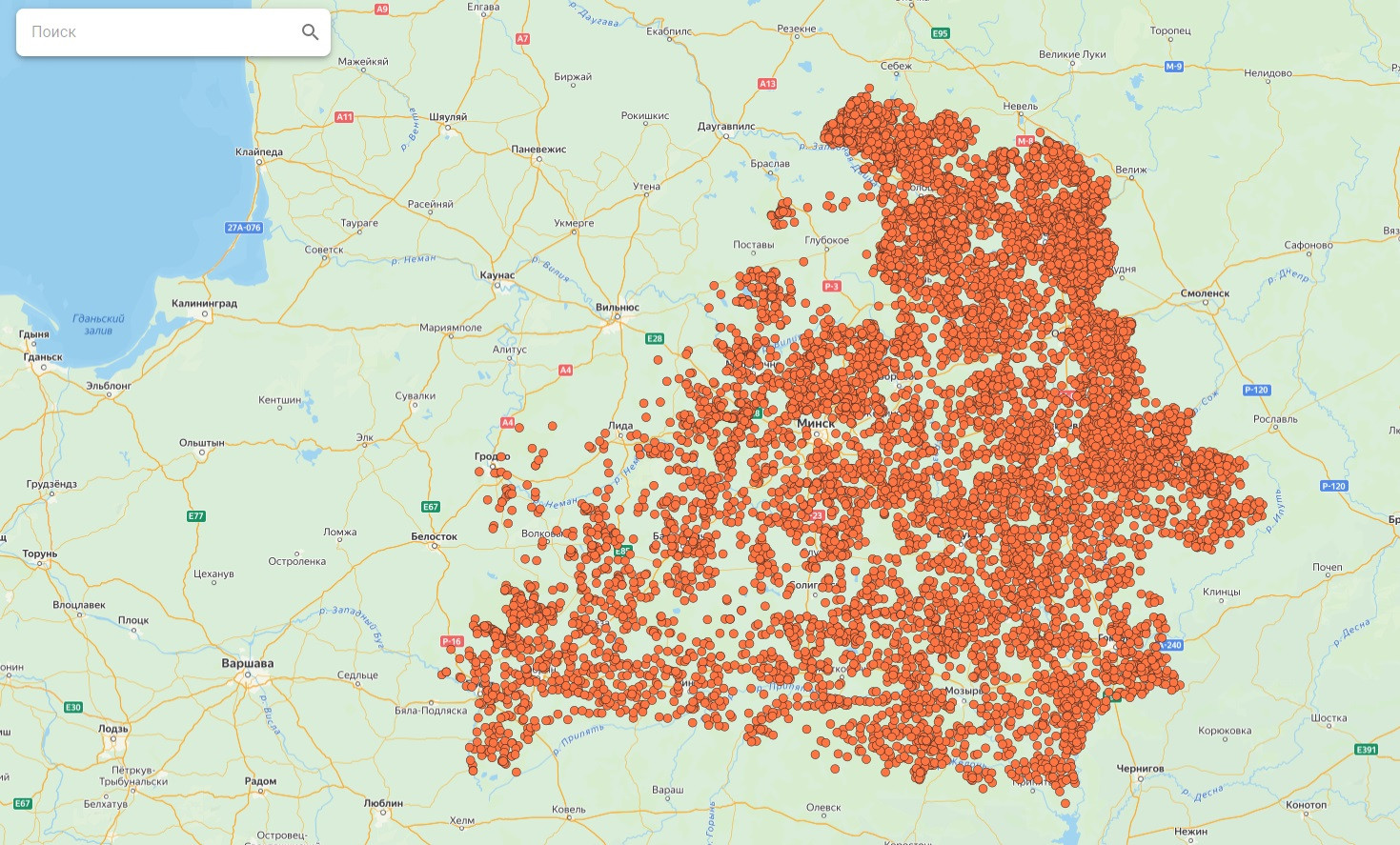

In total, about 9,000 villages and 1,200,000 houses were destroyed in WWII around the country — the victory cost Belarus a quarter of its pre-war population, practically all its intellectual elite perished. Over 80% of buildings and city infrastructure were demolished in the major towns of Minsk and Vitebsk. In Luban district alone, about 3,700 civilians were executed and more than 1,800 were deported to serve as forced laborers in Germany. As a part of the USSR, Belarus won WWII but hardly could anyone think that 70 years later occupation would become our reality again.

In rare cases was the traumatic silence of WWII war generation interrupted by individual voices that articulated the “uncomfortable” past focusing on ordeals one faced. Mikhail Savitsky, a Belarusian painter who went through Düsseldorf, Buchenwald, and Dachau concentration camps. Vasil Bykau, a writer whose reflections on moral dilemmas people confront at war earned him endorsements for the Novel Prize nomination followed by a publication ban in his own native Belarus under Lukashenko’s regime. How much courage must these voices have had to speak up in the country where loyalty to the state was continuously positioned as a duty and doubt — as a crime? Working on the formation of the ideologically “correct” collective image of the glorious past, the Soviet (and after 1991 — Belarusian) state never encouraged veterans and concentration camps survivors to reveal the dark side of the victory — the price they had to pay. War was mostly presented as a celebration, not as suffering, or horror one cannot “unsee”.

I remember that parades pompously held on May 9 were always long-awaited by my Granddad. From early mornings, clean-shaven and smelling Soviet eau de cologne, with medals on his only official jacket diligently ironed by Granny Olga, he would travel as far as the capital — Minsk. He wanted to be recognized, be seen, be given proofs that his sacrificed youth was worth it. At the end of the day, he would bring home “gifts” the district administration yearly handed the veterans — three red carnations and a bottle of vodka. I knew that he, as well as his fellow fighters, focused on what they wanted to focus on: the celebration of peace, “Never again” promise, the hope for a better world. What they did not allow themselves to notice was pompous Victory Day parades gradually turning into the demonstration of military force aimed to scare off potential enemies and desacralize the value of human life.

Vasily Bubich died in 2015. Luckily, he would never learn that his countypeople would find themselves under occupation again with an open military conflict between Russia and Ukraine at its borders. Repressed, silenced memories and unlearnt lessons of history seem to cost us much. According to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, as for April 2023, at least 8,574 civilians were killed during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and 14,441 reported injured. In Belarus, in battlefields international media write little about, more than 1,500 are tortured in prisons with cases of suicide attempts regularly reported. The grandchildren of WWII partisans now have to address and rethink their grandparents’ strategies to continue fighting for freedom.

Grandma Olga who I was named after passed away in April 2020 and when I mentally travel through the memories I have of her, there is one series of episodes that often comes to my mind. Another typical summer holiday spent in village, heat that would cool a bit off only after sunset, the orchestra of singing crickets. My Granny and I used to share the same bedroom with Granddad snoring comfortably in another room nearby. Sometimes, at nightfall, after breaking the silence, in this safe timeless coal dark space of the room she would speak. My eyes and ears wide open, I listened to her harsh composed voice telling me about the youth stolen by the war. It was then that I learnt that most painful memories talk in whispers. And it is the job and duty of ours — listeners — to remember and pass them on. Because it is in most painful memories that most important lessons live.

May, 2023

Minsk-Berlin

More on the topic of memory — The Art of (Not) Forgetting (Instagram), Telegram channel on memory and art — «The Decameron», contact — FB.